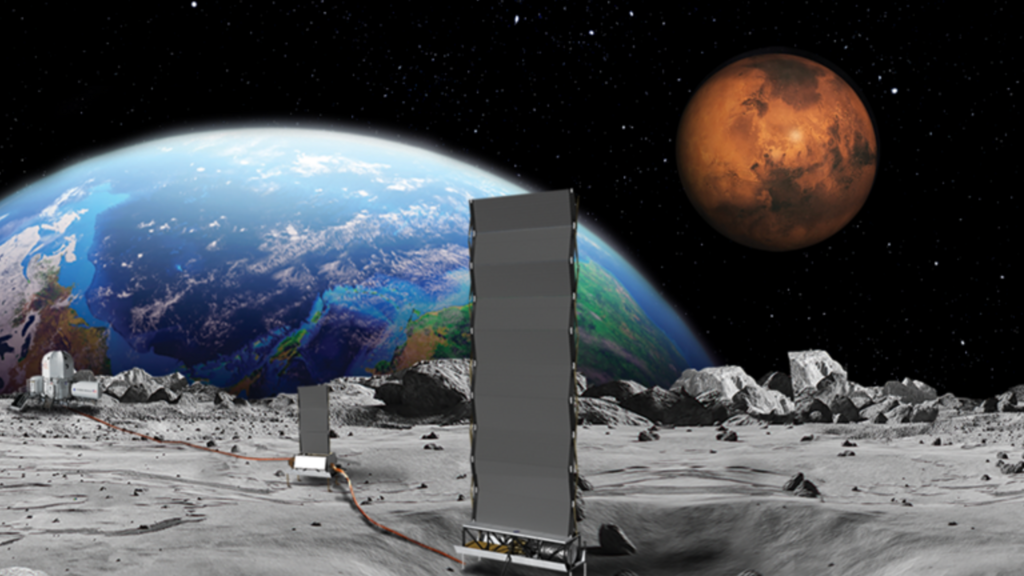

NASA is reportedly accelerating its plans to establish a nuclear reactor on the Moon by 2030, according to reports in US media.

This initiative is a component of the broader US ambition to construct a permanent lunar base for human habitation.

Politico reports that the acting head of NASA referenced similar initiatives by China and Russia, suggesting that these nations “could potentially declare a keep-out zone” on the Moon.

However, the feasibility of this timeline is being questioned, given recent budget reductions at NASA. Some scientists also express concern that geopolitical considerations are driving these plans.

The US, China, Russia, India, and Japan are among the nations engaged in a concerted effort to explore the lunar surface, with some aiming to establish permanent human settlements.

“To properly advance this critical technology to be able to support a future lunar economy, high power energy generation on Mars, and to strengthen our national security in space, it is imperative the agency move quickly,” US transport secretary Sean Duffy, who was appointed temporary head of Nasa by President Donald Trump, wrote to Nasa, according to the New York Times.

Mr. Duffy has requested proposals from commercial entities to develop a reactor capable of generating at least 100 kilowatts of power.

This is a relatively small amount; a typical onshore wind turbine generates 2-3 megawatts.

The concept of employing a nuclear reactor as a power source on the Moon is not novel.

In 2022, NASA awarded three $5 million contracts to companies to design such a reactor.

Furthermore, in May of this year, China and Russia announced plans to construct an automated nuclear power station on the Moon by 2035.

Many scientists concur that nuclear power represents the optimal, or perhaps only, method for ensuring a continuous power supply on the lunar surface.

A single lunar day is equivalent to four Earth weeks, comprising two weeks of continuous sunlight followed by two weeks of darkness. This makes relying on solar power exceedingly difficult.

“Building even a modest lunar habitat to accommodate a small crew would demand megawatt-scale power generation. Solar arrays and batteries alone cannot reliably meet those demands,” suggests Dr Sungwoo Lim, senior lecturer in space applications, exploration and instrumentation at the university of Surrey

“Nuclear energy is not just desirable, it is inevitable,” he adds.

Lionel Wilson, professor of earth and planetary sciences at Lancaster University, believes that deploying reactors on the Moon by 2030 is technically feasible “given the commitment of enough money,” noting that designs for small reactors already exist.

“It’s just a matter of having enough Artemis launches to build the infrastructure on the Moon by then,” he adds, referring to Nasa’s Artemis spaceflight programme that aims to send people and equipment to the Moon.

Safety concerns have also been raised.

“Launching radioactive material through the Earth’s atmosphere brings safety concerns. You have to have a special license to do that, but it is not insurmountable,” says Dr Simeon Barber, planetary science specialist at the Open University.

Mr. Duffy’s directive comes as a surprise following recent turmoil at NASA, after Mr. Trump’s administration announced cuts of 24% to Nasa’s budgets in 2026.

That includes cuts to a significant number of science programmes such as the Mars Sample Return that aims to return samples from the planet’s surface to Earth.

Scientists also express concern that this announcement may be a politically motivated move in the emerging international race to the Moon.

“It seems that we’re going back into the old first space race days of competition, which, from a scientific perspective, is a little bit disappointing and concerning,” says Dr Barber.

“Competition can create innovation, but if there’s a narrower focus on national interest and on establishing ownership, then you can lose sight of the bigger picture which is exploring the solar system and beyond,” he adds.

Mr. Duffy’s comments regarding the potential for China and Russia to “declare a keep-out zone” on the Moon appear to reference an agreement known as the Artemis Accords.

In 2020, seven nations signed the agreement to establish principles on how countries should co-operate on the Moon’s surface.

The accords include so-called safety zones to be established around operations and assets that counties build on the Moon.

“If you build a nuclear reactor or or any kind of base on the moon, you can then start claiming that you have a safety zone around it, because you have equipment there,” says Dr Barber.

“To some people, this is tantamount to, “we own this bit of the moon, we’re going to operate here and and you can’t come in”,” he explains.

Dr. Barber notes that several hurdles must be overcome before a nuclear reactor can be deployed on the Moon for human use.

Nasa’s Artemis 3 aims to send humans to the lunar surface in 2027, but it has faced a series of set-backs and uncertainty around funding.

“If you’ve got nuclear power for a base, but you’ve got no way of getting people and equipment there, then it’s not much use,” he added.

“The plans don’t appear very joined up at the moment,” he said.

The four-person crew, who launched a day late due to weather, will relieve members of the previous SpaceX mission onboard the station.

Nasa-Isro joint mission Nisar will record the minutest of changes in the land, sea or ice sheets.

The Axiom-4 (Ax-4) mission with Shubhanshu Shukla splashed down off the coast of California.

The Buck Moon is named because traditionally July is the time when a male deer grows full antlers.

Shubhanshu Shukla becomes the first Indian on ISS as the mission docks with the orbiting laboratory.