“Let me tell you a secret. Your nana (grandfather) helped Jewish families escape the Nazis.”

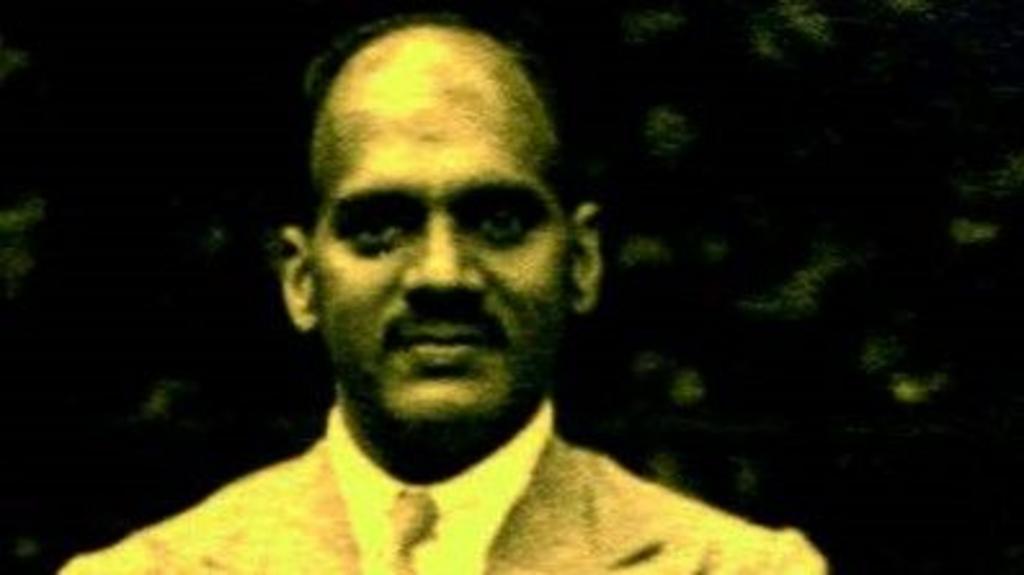

That single sentence from his mother propelled Vinay Gupta on a journey into his grandfather’s past. What he unearthed was a narrative more compelling than fiction: a little-known act of heroism by an Indian businessman who risked everything to save strangers during Europe’s darkest period.

This wasn’t merely compassion; it involved logistics, risk assessment, and unwavering resolve. Back in India, Kundanlal established businesses to employ Jewish individuals and constructed homes to accommodate them – only to witness the British authorities designate them as “enemy aliens” and detain them following the outbreak of World War Two.

Kundanlal’s life unfolds like an epic: a humble beginnings in Ludhiana, married at 13, who engaged in diverse trades from timber and salt to laboratory equipment and bullock-cart wheels. He also managed a clothing enterprise and a matchstick factory. As a top student in Lahore, he joined the colonial civil service at 22, only to resign and dedicate himself to the freedom movement and establishing factories.

He interacted with Indian independence leader and future Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and encountered actress Devika Rani on a steamer to Europe.

In “A Rescue In Vienna,” a family memoir, Gupta meticulously reconstructs his grandfather’s remarkable rescue efforts on foreign soil, drawing from family letters, survivor testimonies, and historical records.

Amidst the backdrop of Hitler’s 1938 annexation of Austria, Kundanlal, a machine tool manufacturer from Ludhiana in Punjab, discreetly offered Jewish professionals positions in India to facilitate their acquisition of life-saving visas. He provided employment, sustenance, and housing for these families in India.

Kundanlal is credited with rescuing five families.

Fritz Weiss, a 30-year-old Jewish lawyer, sought refuge in a hospital, feigning illness. Coincidentally, Kundanlal was also at the same hospital seeking treatment for his own ailment.

After the Nazis compelled Weiss to clean the streets in front of his residence, Kundanlal offered him a lifeline: a job at the fictitious “Kundan Agencies,” which secured him a visa to India.

Alfred Wachsler, a skilled woodworker, encountered Kundanlal while accompanying his pregnant wife for medical examinations. Promised a future in furniture and sponsorship for emigration, his family became one of the Jewish households to arrive in India between January 1938 and February 1939.

Hans Losch, a textile technician, responded to Kundanlal’s advertisement in an Austrian newspaper seeking skilled laborers. Offered a managerial position at the imaginary “Kundan Cloth Mills” in Ludhiana – complete with housing, profit sharing, and safe passage – he embraced the opportunity for a fresh start.

Alfred Schafranek, formerly the owner of a 50-employee plywood factory, presented his skills to Kundanlal and was offered a role in establishing India’s most advanced plywood unit. His entire family, including his mechanic brother Siegfried, was rescued.

And Siegmund Retter, a machine tools businessman, was among the first individuals Kundanlal approached. As his business faltered under Nazi rule, Kundanlal initiated arrangements for his relocation to India to rebuild his life.

It all began with a hospital bed in Vienna.

Battling diabetes and hemorrhoids, Kundanlal, then 45, sought innovative treatments and learned about a specialist in Vienna. In 1938, during his recovery from surgery, he met Lucy and Alfred Wachsler, a young couple expecting their first child. They shared accounts of escalating antisemitic violence and the destruction of Jewish lives.

Over the ensuing months, he engaged with other men. Inspired by this initial success, Kundanlal placed newspaper advertisements seeking skilled workers willing to relocate to India. Among the respondents were Wachsler, Losch, Schafranek, and Retter. Kundanlal extended job offers, financial guarantees, and assistance in securing Indian visas to each of them.

“A striking aspect of all of Kundanlal’s elaborate scheming on behalf of these families was how close mouthed he remained, keeping up appearances of technology transfer to India until the very end,” Gupta writes.

“He did not share his intent or plans with any Indian or British officials. His family learned of his plans only when he returned home months later.”

In October 1938, Losch became the first of Kundanlal’s recruits to arrive in Ludhiana.

He was welcomed into Kundanlal’s home – but found little comfort in the quiet town, writes Gupta. With no Jewish community, no cultural life, and a struggling cloth mill, Losch left within weeks for Bombay (now Mumbai), citing poor working conditions and little chance of profit. He never returned.

Weiss lasted even less – just under two months. The company created for him, Kundan Agencies, never took off. He soon moved to Bombay, found work in flooring, and by 1947 had relocated to England.

Despite their departures, Kundanlal bore no resentment, writes Gupta.

“My aunt told me that on the contrary, Kundanlal had been embarrassed that he could not provide a lifestyle and social environment more suited to Vienna, and felt that if he had, the two men may have stayed on in Ludhiana.”

Not all stories ended this way.

Alfred and Lucy Wachsler, with their infant son, arrived by sea, rail, and road – finally stepping off the train at Ludhiana.

They moved into a spacious home Kundanlal built for them next door to another, prepared for the Schafraneks. Alfred quickly set up a furniture workshop, using Burmese teak and local Sikh labor to craft elegant dining sets – one of which still survives in the author’s family.

In March 1939, Alfred Schafranek, his brother Siegfried, and their families arrived from Austria. They launched one of India’s earliest plywood factories in a shed behind the two homes.

Driven and exacting, Alfred pushed untrained workers hard, determined to build something lasting. Gupta writes, the work was intense, the Punjab heat unfamiliar, and the isolation palpable – especially for the women, confined mostly to domestic life.

As the months passed in Ludhiana, the initial relief gave way to boredom.

The men worked long hours, while the women, limited by language and isolation, kept to household routines.

In September 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. Days later, Britain declared war on Germany – the British parliament pulled India into the conflict. Over 2.5 million Indians would serve in the war, 87,000 never returned.

In Ludhiana, the reality of war hit fast.

By 1940, new policies ordered all German nationals – Jewish or not – into internment camps.

The Wachsler and Schafranek families were forcibly relocated to the Purandhar Internment Camp near Poona (now Pune), housed in bare barracks with kerosene lamps and minimal comforts. They had committed no crime – only carried the wrong passport.

Eventually, release became possible – if they could find paid work.

Alfred and Siegfried Schafranek secured roles managing a new plywood business in Bangalore and moved there with their families, starting all over again. The Wachsler family left the camp in 1942 after Alfred found a job in Karachi. The two families never met again.

Purandhar Camp closed in 1946, nearly a year after the war ended.

In 1948, Alfred Wachsler’s cousin sponsored US refugee visas for the family. That October, they flew out of Karachi, never to return to India. The Schafraneks relocated to Australia in 1947 after a successful plywood venture in Bangalore.

While researching the book, Gupta met Alex Wachsler – whose father, Alfred, had also built the Burmese teak desk Kundanlal once used in his tiny 120 sq ft office. (Alfred died in 1973.)

“Despite living in US since the age of 10, and now into his eighties, Alex Wachsler still pines for his life in India, eats at Indian restaurants, delights in meeting Indians and surprises them with his knowledge of Urdu,” writes Gupta.

Back in Ludhiana, Kundanlal opened a school for his daughters at home, soon expanding it into one of Punjab’s oldest schools – still running today with 900 students. His wife, Saraswati, grew increasingly withdrawn and battled depression.

Kundanlal and Saraswati had five children, including four daughters. In 1965, Saraswati died after a tragic fall from their terrace. She spent her final years in silence, emotionally distanced from the family. Kundanlal passed away a year later, aged 73, from a heart attack.

“The notion of a ‘passive bystander’ was anathema to Kundanlal. If he saw something, or someone, that required attention, he attended to it, never intimidated by the enormity of the problem,” writes Gupta.

A fitting epitaph for a man whose legacy was not just business, but quiet defiance, compassion, and conviction.

Cirencester’s Old Station, designed by Brunel, will reopen as part of the town’s history festival.

Jasprit Bumrah has his first wicket of the innings with a superb yorker that beats Brydon Carse all ends and leave England 182-9.

Watch as India’s Washington Sundar removes Joe Root & Jamie Smith in quick succession to Leave England in trouble at 164-6.

Harry Brook goes for an aggressive sweep and sees his middle stump knocked back by Akash Deep as England fall to 87-4 at Edgbaston.

Mohammed Siraj gets in England’s Ben Duckett face as he celebrates a wicket in the third Test at Edgbaston.