Researchers have revealed that high-resolution imaging of tattoos discovered on a 2,500-year-old Siberian “ice mummy” showcases intricate designs that would pose a significant challenge even for contemporary tattoo artists.

The elaborate tattoos adorning the woman’s body, featuring leopards, a stag, a rooster, and a mythical creature that is part-lion and part-eagle, offer valuable insights into an ancient warrior culture.

In an effort to understand the techniques employed in creating these tattoos, archaeologists collaborated with a tattooist who recreates ancient skin decorations on his own body.

The tattooed woman, estimated to be around 50 years old, belonged to the Pazyryk people, a nomadic, horse-riding group that inhabited the vast steppe between China and Europe.

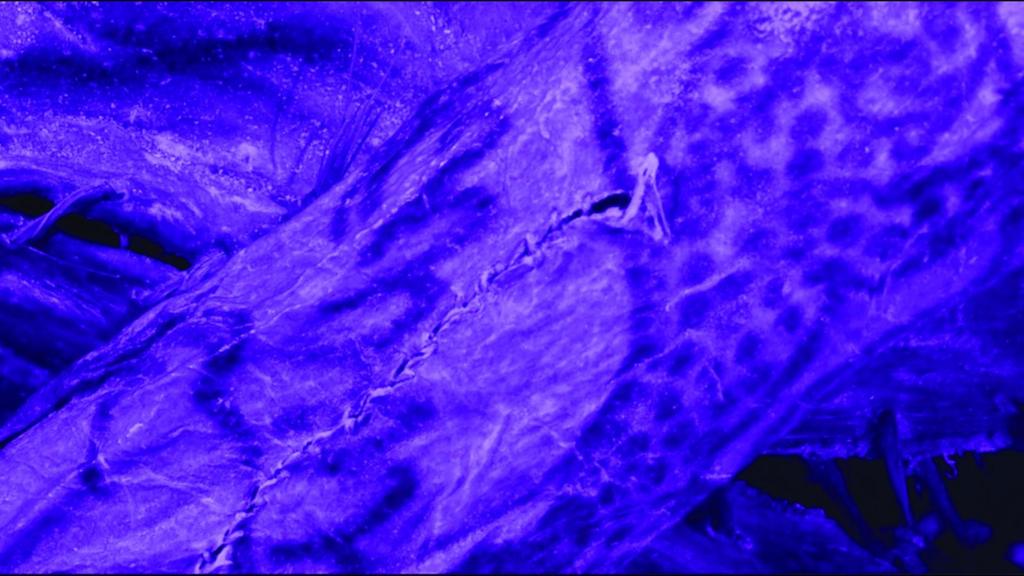

The scans unveiled “intricate, crisp, and uniform” tattooing that was previously undetectable to the naked eye.

“The insights really drive home to me the point of how sophisticated these people were,” Dr. Gino Caspari from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and the University of Bern, the lead author of the study, told BBC News.

Due to the destructive nature of time, obtaining detailed information about ancient social and cultural practices is often difficult. Gaining access to the intimate details of an individual’s life is even more challenging.

The Pazyryk “ice mummies” were discovered in ice tombs located in the Altai Mountains of Siberia during the 19th century, but observing their tattoos has proven difficult.

Experts at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, have now employed near-infrared digital photography to produce high-resolution scans of the decorations for the first time.

“This made me feel like we were much closer to seeing the people behind the art, how they worked and learned. The images came alive,” Dr. Caspari stated.

The Pazyryk woman’s right forearm featured an image of leopards surrounding the head of a deer.

On her left arm, the mythical griffin, a creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle, appears to be engaged in combat with a stag.

“Twisted hind bodies and really intense battle scenes of wild animals are typical of the culture,” Dr. Caspari noted.

However, the woman also had a rooster tattooed on her thumb, which Dr. Caspari describes as exhibiting “an intriguing style with a certain uniqueness.”

The team collaborated with researcher Daniel Riday, who recreates ancient tattoo designs on his own body utilizing historical methods.

His insights into the scans led them to conclude that the quality of the work differed between the two arms, suggesting either that different individuals created the tattoos or that mistakes were made.

“If I was guessing, it was probably four and a half hours for the lower half of the right arm, and another five hours for the upper part,” he estimates.

“That’s a solid commitment from the person. Imagine sitting on the ground in the steppe where there’s wind blowing all that time,” he suggests.

“It would need to be performed by a person who knows health and safety, who knows the risks of what happens when the skin is punctured,” he adds.

By analyzing the marks on the woman’s skin, the team believes that the tattoos were likely stenciled onto the skin before being tattooed.

They theorize that a needle-like tool with multiple small points, possibly made from animal horn or bone, was used, in addition to a single-point needle. The pigment was likely derived from burnt plant material or soot.

Dr. Caspari, who does not have tattoos himself, emphasizes that the research sheds light on an ancient practice that remains significant for many people worldwide today.

“And back in the day it was already a really professional practice where people put a lot of time and effort and practice into creating these images and they’re extremely sophisticated,” he adds.

Some of the tattoos appear to have been cut or damaged during the preparation of the body for burial.

“It suggests that tattoos were really something for the living with meaning during life, but that they actually didn’t really play much of a role in the afterlife,” Dr. Caspari explains.

The findings have been published in the journal Antiquity.

Get our flagship newsletter with all the headlines you need to start the day. Sign up here.

Prof Michele Dougherty is the first woman to be appointed to the influential post.

The model, made of plastic collected on the Darwin200 voyage, is inspired by a Barbie doll of Dame Jane Goodall.

The research programme aims to tackle problems associated with heat, drought and disease.

Teachers at Hautlieu say STEM on Track has made a big difference for their students.

A new system fills in missing words from ancient inscriptions carved on monuments and everyday objects.