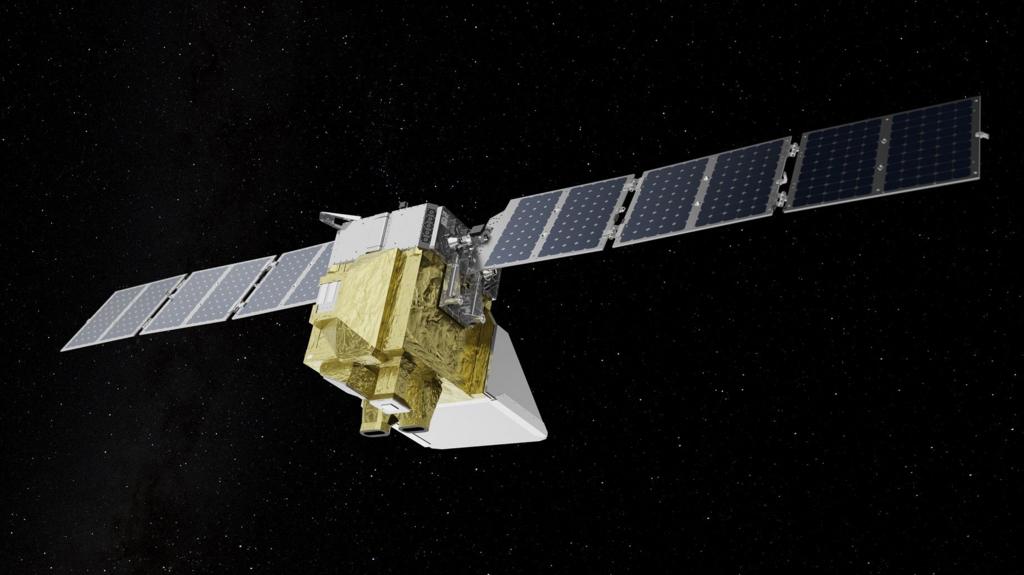

A satellite, valued at $88 million (£65 million), designed to detect methane emissions from oil and gas operations, has been lost in space, representing a significant setback for global climate initiatives.

MethaneSat, supported by Google and Jeff Bezos, was launched just last year aboard a SpaceX rocket.

The satellite was intended to gather data for five years on sources of methane, a potent greenhouse gas responsible for approximately one-third of human-induced warming, to help reduce emissions from the worst offenders.

The Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), the NGO overseeing the project, reported that communication was lost ten days ago and an investigation into the cause is underway.

Methane is the most powerful of the greenhouse gases; while it persists in the atmosphere for a shorter duration than carbon dioxide, it traps significantly more heat, roughly 28 times more over a 100-year period.

Despite international pledges to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030, levels continue to rise year-on-year, making the target increasingly unattainable, according to the European Space Agency.

Major methane sources include oil and gas production, agricultural activities, and decomposition processes in landfills.

Currently, many methane-monitoring satellites are operated by private entities, which reduces transparency regarding the largest sources of methane emissions.

MethaneSat was developed over several years by the EDF, and upon its launch, the organization made much of its data publicly accessible, facilitating review by governments and researchers.

The project secured backing from a consortium of tech leaders, including Google and Jeff Bezos, who collectively contributed $88 million.

The satellite’s instruments were among the most advanced globally, capable of detecting even small methane sources, as well as “super-emitters.”

Enhanced sensitivity is critical for identifying emissions from agriculture, which are typically more diffuse compared to those from oil and gas production.

Google stated at the time of launch that it hoped the project would “fill gaps between existing tools.”

The company was leveraging its artificial intelligence capabilities to process data and create a global methane map.

However, after only one year in orbit of a projected five-year mission, communication with MethaneSat was lost.

The EDF team suspects the satellite has suffered a power failure, stating that “it is likely not recoverable.”

The organization added that some software components might be salvaged but noted it was too early to determine whether a replacement satellite would be launched.

“Addressing the climate challenge necessitates bold action and risk-taking, and this satellite was at the forefront of science, technology, and advocacy,” the EDF stated.

Another significant public source of methane data is hosted by CarbonMapper. One of its data sources is the TROPOMI instrument aboard the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite. While this continues to transmit data, its seven-year program was scheduled to conclude in October.

The remaining operational lifespan of this instrument is uncertain, further curtailing global capabilities to monitor methane emissions.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to keep up with the latest climate and environment stories with the BBC’s Justin Rowlatt. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.

Steve Backshall says when it comes to climate change young people need to feel empowered to act.

A Cambridge start-up is one firm taking on the challenge of improving battery charging technology.

It says drought has compounded poverty, hunger, and energy insecurity worldwide.

We take a look at river, reservoir and groundwater levels after a particularly dry few months.

The garden will feature 300 species, each selected for their climate resilience and biodiversity.