“One might assume this is solely about Andrew,” a senior Whitehall source remarked.

“However, consider this a pivotal moment in the dynamic between the Palace and Parliament.”

Will this royal controversy usher in a new chapter? Despite their customary reluctance to comment, might politicians become more inclined to highlight the monarchy’s shortcomings and more willing to voice their concerns?

“Nice try!” was then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s rejoinder when questioned by reporters about the now-infamous interview with the individual, who until recently held the title of Prince Andrew, back in 2019.

That response encapsulates the prevailing sentiment for years. Ministers have historically preferred to avoid commenting on the matter at all costs.

“It was more than just reluctance; it was a no-win situation,” a former No. 10 official recalled. “You either risked incurring the Palace’s displeasure or appearing to defend the indefensible.”

This avoidance strategy extended beyond the protracted Andrew saga. For many years, the prevailing convention dictated that senior politicians aspiring to government proximity should maintain diplomatic silence regarding the royals, offering only bland praise or supportive, muted affirmations.

The convention operated reciprocally, with the Royal Family abstaining from public pronouncements on political matters. Mutual, courteous acknowledgement was the established norm, deliberately so: “Don’t upset the Queen, don’t upset the King.”

Within our political framework, comparable unwritten rules are rare. The former No. 10 source noted that prime ministers are seldom explicitly instructed against certain actions, but when the subject turns to the royals, aides and officials are “preprogrammed” to advise: do not engage.

Of course, notable exceptions have always existed.

Former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, a republican, questioned whether the royal family’s scale should be reduced.

Boris Johnson angered the Palace when he prorogued Parliament for weeks, suspected of attempting to prevent MPs from thwarting his Brexit ambitions. The Palace found this overtly political act deeply unsettling.

David Cameron received a rebuke for claiming the late Queen “purred” on the phone when he informed her of the Scottish referendum result.

Green Party leader Zack Polanski affirmed his party’s republican stance, noting the presence of numerous republicans within Labour, the SNP, and the Liberal Democrats, though these are not the parties’ official positions.

In reality, for those in or near positions of power, the monarchy is not merely a political reality but an integral part of the system. The reason? The crown is featured on government letterheads, legal documents, and ministers’ dispatch boxes. The government is, in effect, His or Her Majesty’s administration.

Ministers are appointed by the Crown, a fact that extends beyond mere abstraction. Senior politicians on the Privy Council regularly interact with the monarch. The Prime Minister famously holds a weekly private audience with the King.

Thus, the government and the Palace are intrinsically linked through processes and personal relationships. Insiders emphasize that these tangible connections are another reason to avoid taking potshots.

However, recent weeks have witnessed a demonstrably bolder attitude within Parliament. The steady stream of revelations regarding Andrew’s conduct has sparked an unusual level of discussion. MPs have attempted to compel a change in the law to strip him of his titles.

The Liberal Democrats considered using their allotted time in the House of Commons to debate escalating the pressure. The influential Public Accounts Committee has demanded answers regarding Andrew’s peppercorn rent for his Windsor residence. Even as his brother arranges for removal vans, the PAC awaits responses to its inquiries and may launch a broader financial investigation pending those replies.

While still unlikely, the committee’s MPs could even subpoena Andrew to testify.

American politicians have threatened similar action, and UK Trade Minister Chris Bryant stated on Friday morning that Andrew should comply if requested, as any “decent person” would.

Just weeks prior, such comments from a British government member would have been scarcely imaginable.

The nature of the allegations, and arguably the Palace’s prolonged hesitation to take decisive action, have shifted the mood, reflecting, as politicians often do, public sentiment.

“We strongly support the Royal Family and the King,” an opposition source noted, “but many people we spoke with while canvassing were so dissatisfied that we felt the issue needed resolution.”

Discomfort surrounding royal conduct has spread beyond usual critics, with Robert Jenrick and Sir Ed Davey’s remarks sending “shockwaves.”

Sources suggest that messages were also being discreetly conveyed from the government. One source noted, “People politely telling the Palace that this isn’t going away and is difficult—the government saying ‘eek, this isn’t going away’—will have played a part.”

Furthermore, the royal uproar has proven remarkably convenient for the government this week, dominating headlines while Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ conduct faced scrutiny.

During royal scandals, “You breathe a sigh of relief as you guys – the media – go crackers over something else,” a former No. 10 official stated.

Reeves admitted to breaking the rules and failed to present a consistent narrative initially. Had the King’s decision occurred a few days earlier or later, the Chancellor’s embarrassment might have escalated into a more significant scandal.

It would be inaccurate to suggest politicians were solely responsible for Andrew’s removal. The King faced unprecedented heckling, and concerns regarding Andrew’s behavior have persisted for years, accompanied by a series of allegations.

Several weeks ago, Virginia Giuffre’s family appeared on my show and argued that Lord Mandelson should never have served as the UK ambassador to the US.

However, the roles of Parliament and politicians were significant, according to a source. Another Whitehall insider noted that the issue originated in Parliament, and the Palace “would have been aware that it was becoming a bigger issue” there.

While the monarch is technically the ultimate authority, Parliament controls the Sovereign Grant and possesses the power to scrutinize the Palace’s expenditures.

What happens now? Some MPs may have developed a taste for exerting pressure on the royals. A comprehensive investigation into Andrew’s finances remains possible. Calls for a debate regarding his removal from the line of succession have already emerged, though this would necessitate a legal amendment, a prospect unlikely to appeal to a weakened government seeking to avoid deeply divisive issues.

However, one insider suggests, “There are numerous politicians in both houses who have long sought to address this issue, and Andrew’s actions have now provided them with an opportunity to fully engage.”

Perhaps royal controversies will become a more commonplace feature of our political landscape.

The “blanket blah-blah-blah, we can’t comment” approach, as described by a former Downing Street figure, may have run its course.

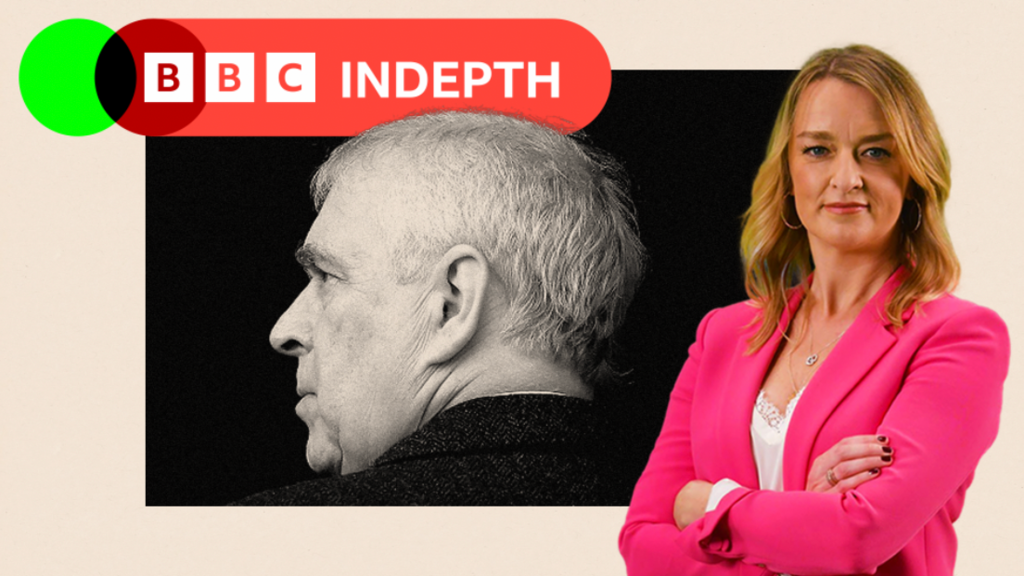

BBC InDepth is the destination on our website and app for insightful analysis, offering fresh perspectives that challenge conventional wisdom and in-depth reporting on the day’s most critical issues. Sign up for notifications to receive alerts whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.

The scandal surrounding Andrew, though self-inflicted, has significantly impacted his immediate family.

The government has stated there are no plans to formally remove Andrew from the line of succession.

Lee White sent 109 threatening emails to Rosena Allin-Khan, the Labour MP for Tooting.

Royal historian Kelly Swaby described Buckingham Palace’s statement as “very brutal” to the BBC.

The expansive Norfolk estate houses several properties – here’s a look at where Andrew may be relocating.