The Armagh Observatory is commemorating a significant meteorological milestone, marking 230 years of uninterrupted weather observation.

This unbroken tradition of meticulously handwritten data constitutes the longest continuous weather record in the UK and Ireland.

Special events are being held at the Armagh Observatory on Monday to celebrate this noteworthy anniversary.

While automated weather stations are now the norm for data collection, Armagh remains an exception, preserving the vital human element.

The first handwritten entry dates back to the evening of July 14, 1795, when temperature and air pressure readings were carefully noted on a graph at the observatory overlooking the city of Armagh.

This practice has been diligently maintained every day since, for the past 230 years.

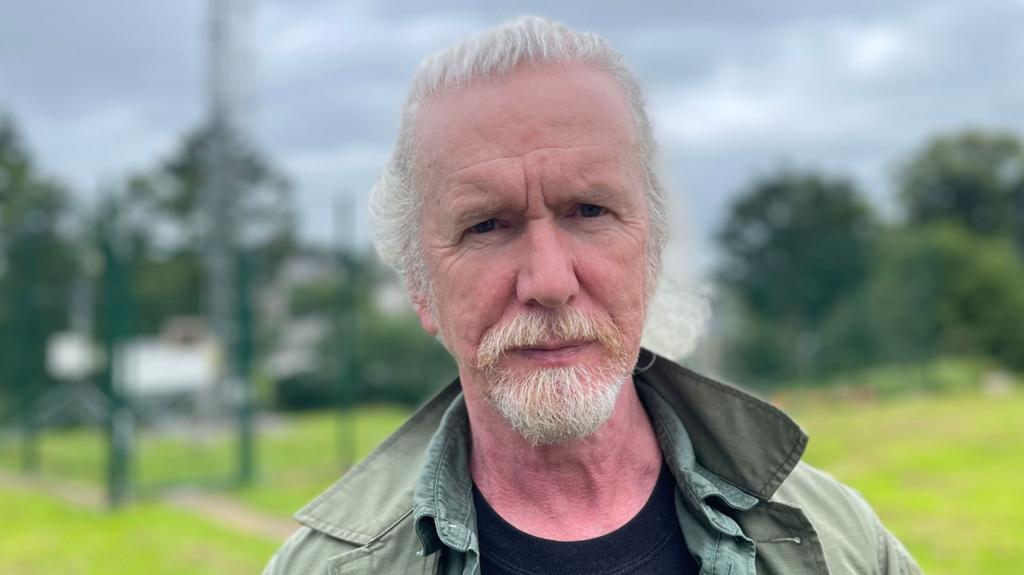

Currently, Shane Kelly serves as the principal meteorological observer at the observatory.

Since 1999, his duties include accessing the Stevenson screen, which houses delicate thermometers, and recording the day’s readings in the handwritten ledger.

He has personally contributed more data entries than any of his 17 predecessors.

“You become ingrained in the infrastructure,” Kelly notes.

“The observatory encompasses both astronomy and meteorology, and after so many years, I feel like I’m part of the very fabric of the place.”

Having observed the weather in Armagh for a quarter of a century, Kelly has noticed shifts in weather patterns.

“The seasons aren’t as clearly defined as they once were,” he explains.

“We’re increasingly experiencing one extended season, punctuated by brief periods of snow or sunshine.”

The 230-year weather record from Armagh originates from a time when meteorology was in its infancy.

Beginning in 1795, it predates Luke Howard’s groundbreaking “Essay on the Modification of Clouds” by eight years.

Howard’s influential work established the cloud naming system that, with minor adjustments, remains in use today.

The observers in Armagh have also made their own contributions to the advancement of the science.

The records document significant aurora events and some of the earliest observations of noctilucent clouds, a characteristic feature of clear summer nights in Northern Ireland.

The entry for January 6, 1839, describes a “tremendous gale in the night.”

This understated description refers to a storm that reportedly caused the deaths of 250 to 300 people.

In 1908, when pensions were introduced for individuals over 70 in Ireland, memories of “Oíche na Gaoithe Móire” (the Night of the Big Wind) were used as a verification question for those lacking birth certificates.

It may also have inspired Romney Robinson, the observatory’s third director, to develop the four-cup anemometer, a device for accurately measuring wind speed.

Dr. Rok Nežič, the tours and outreach officer at Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, explained that while methods for measuring wind speed existed prior to the four-cup anemometer, “they lacked precision.”

“Robinson conceived of a device capable of capturing wind from any direction,” said Dr. Nežič, who is also a trained weather observer.

“The design has undergone only minor modifications since its invention in 1845, and we continue to use it today.

From Armagh, it has been adopted worldwide.”

While the unbroken sequence of data recorded in Armagh has primarily been documented by men, its preservation is largely attributed to one remarkable woman.

In 1917, Theresa Hardcastle arrived in Armagh from England with her children.

Her husband, Joseph, had been appointed as the next director of the observatory, and Theresa came to oversee repairs to their future residence.

Tragically, Joseph passed away before he could join her.

Despite her bereavement, Theresa remained in Armagh and continued to make and record the daily weather observations.

Jessica Moon, from the observatory and planetarium, describes Theresa as the “unsung hero” of the Armagh story.

“No one would have expected her to take on that role,” she said.

“It was entirely outside her expected duties. She is a crucial figure in this narrative.”

Today, many of the weather observers trained by Shane Kelly come from across the globe.

For the current observatory director, Professor Michael Burton, the hands-on gathering of weather data is an integral part of the training process for PhD students based in Armagh.

“The act of measurement itself is at the core of science,” he stated.

“But it is not a straightforward process. The experience of engaging directly with the data – of getting your hands dirty, so to speak – is essential for truly understanding what is happening.

“Measuring the weather offers valuable lessons about science… It enhances your comprehension of the data.”

Given its vital role in training the scientists and astronomers of the future, Armagh’s enduring human connection to the weather of the past appears set to continue for many years to come.

More than 90 Royal Black Institution preceptories and marching bands took part in the annual event.

Five young children were rescued by two off-duty nurses after getting into difficulty off the County Down coast.

A shop, scoreboard and signage at Lámh Dhearg GAC in Hannahstown were destroyed in the attack on Saturday evening.

A council has received funding for a high-powered washing machine to remove chewing gum on its streets.

Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK and Ireland with no publicly funded service to get intimate images taken down or deleted.