New research reveals that zooplankton, often overlooked creatures commonly sold as aquarium food, play a crucial role in mitigating global warming through their extensive migration patterns.

These diminutive “unsung heroes” consume substantial amounts of food and accumulate fat reserves during the spring season. Subsequently, they descend hundreds of meters into the Antarctic depths, where they metabolize these fat stores.

Researchers have found that this process sequesters a quantity of carbon equivalent to the annual emissions of approximately 55 million gasoline-powered vehicles, effectively preventing its release into the atmosphere and further contributing to global warming.

This carbon sequestration capacity is far greater than previously estimated. However, concurrent with this discovery, the threats to zooplankton populations are escalating.

Scientists have dedicated years to studying the annual migration of these organisms in Antarctic waters, also known as the Southern Ocean, and its implications for climate change.

Dr. Guang Yang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the lead author of the study, described the findings as “remarkable,” emphasizing the need to reassess the Southern Ocean’s carbon storage potential.

Dr. Jennifer Freer from the British Antarctic Survey, a co-author of the study, highlighted the zooplankton’s unique life cycle, stating, “The animals are an unsung hero because they have such a cool way of life.”

Despite their significance, zooplankton remain underappreciated compared to more charismatic Antarctic fauna such as whales and penguins.

They are often recognized, if at all, as a type of fish food readily available for purchase online.

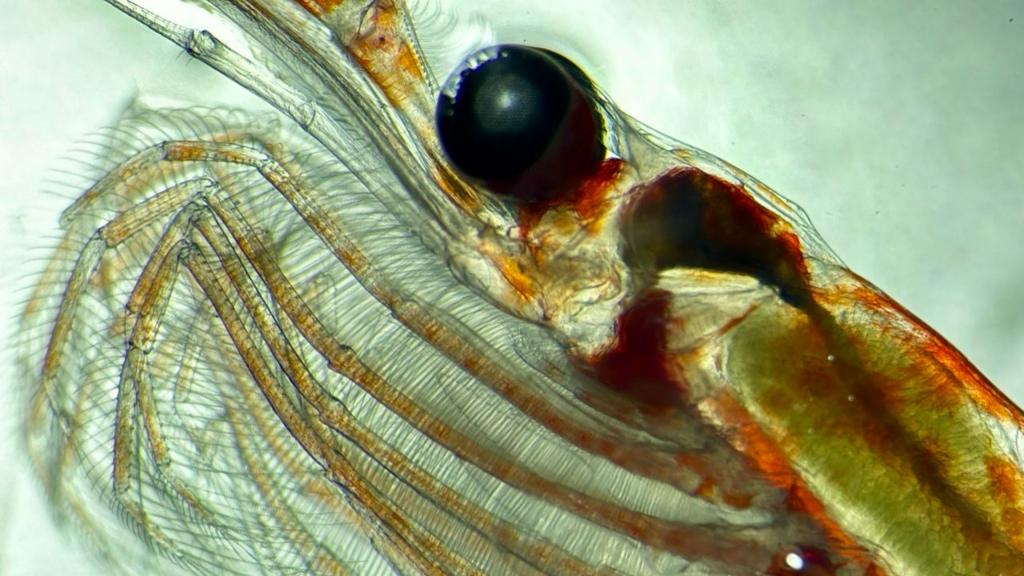

However, their life cycle is both peculiar and captivating. Consider the copepod, a zooplankton species distantly related to crabs and lobsters.

These creatures, measuring a mere 1-10mm in length, spend the majority of their lives in a quiescent state at depths ranging from 500m to 2km.

Professor Daniel Mayor, who photographed them in Antarctica, noted that microscopic images reveal substantial fat reserves within their bodies, including prominent fat droplets in their heads.

Without their critical function, the Earth’s atmosphere would be substantially warmer.

Oceans worldwide have absorbed 90% of the excess heat generated by human fossil fuel consumption. The Southern Ocean accounts for approximately 40% of this absorption, largely attributed to zooplankton activity.

Significant global investment is directed toward elucidating the precise mechanisms by which these organisms store carbon.

Scientists were previously aware of the role of zooplankton in daily carbon storage, wherein carbon-rich waste produced by these animals sinks to the deep ocean.

However, the carbon sequestration resulting from the zooplankton’s seasonal migration in the Southern Ocean had not been quantitatively assessed.

The latest research focused on copepods, as well as other zooplankton types including krill and salps.

These organisms consume phytoplankton on the ocean surface, which convert carbon dioxide into organic matter through photosynthesis, subsequently transforming into fat within the zooplankton.

Professor Daniel Mayor from the University of Exeter, who was not involved in the study, explained, “Their fat is like a battery pack. When they spend the winter deep in the ocean, they just sit and slowly burn off this fat or carbon.”

He added, “This releases carbon dioxide. Because of the way the oceans work, if you put carbon really deep down, it takes decades or even centuries for that CO2 to come out and contribute to atmospheric warming.”

The research team calculated that this process, termed the seasonal vertical migration pump, annually transports 65 million tonnes of carbon to depths of at least 500m below the ocean surface.

Copepods were found to contribute the most to this process, followed by krill and salps.

This carbon sequestration is roughly equivalent to the annual emissions from 55 million diesel vehicles, according to the US EPA’s greenhouse gas emissions calculator.

The study incorporated data dating back to the 1920s to quantify this carbon storage, also known as carbon sequestration.

Scientific investigation continues as researchers strive to gain further insights into the intricacies of the migration cycle.

Earlier this year, Dr. Freer and Professor Mayor spent two months aboard the Sir David Attenborough polar research vessel near the South Orkney Islands and South Georgia.

The scientists used large nets to capture zooplankton, bringing the animals onboard for study.

“We worked in complete darkness under red light so we didn’t disturb them,” said Dr. Freer.

She added, “Others worked in rooms kept at 3-4C. You wear a lot of protection to stay there for hours at a time looking down the microscope.”

However, rising water temperatures and commercial krill harvesting pose potential threats to the future of zooplankton populations.

“Climate change, disturbance to ocean layers and extreme weather are all threats,” explained Professor Atkinson.

These factors could reduce zooplankton populations in Antarctica and limit the amount of carbon stored in the deep ocean.

Krill fishing companies harvested nearly half a million tonnes of krill in 2020, according to the UN.

While permitted under international law, this practice has been criticized by environmental campaigners, as highlighted in the recent David Attenborough Ocean documentary.

The scientists assert that their new findings should be integrated into climate models to enhance the accuracy of future global warming projections.

“If this biological pump didn’t exist, atmospheric CO2 levels would be roughly twice those as they are at the moment. So the oceans are doing a pretty good job of mopping up CO2 and getting rid of it,” explained co-author Professor Angus Atkinson.

The research is published in the journal Limnology and Oceanography.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to receive exclusive insights on the latest climate and environment news from the BBC’s Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt, delivered to your inbox every week. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.