Listen to Ankur read this article

Chongqing, a sprawling city in southwestern China, presents a breathtaking urban landscape. Its mountainous terrain, crisscrossed by rivers, is unified by extensive elevated roadways; trains even traverse some buildings.

This striking urban architecture has become a popular subject for TikTokers, generating millions of views and considerable online buzz.

However, Chongqing also served as the destination for a significant UK delegation – the largest British civic group ever to visit China – on a less publicized trip.

The March visit received substantial coverage in Chinese media, though it remained relatively low-key in the UK. Its impact on participating UK politicians, however, was profound.

“[The city is] what happens if you take the planning department and just say ‘yes’ to everything,” remarked Howard Dawber, London’s Deputy Mayor for Business. “It’s just amazing.”

The delegation visited southern Chinese cities, engaging with Chinese mayors and tech leaders. One deputy mayor’s visit resulted in purchasing a phone from the Chinese brand Honor – a notable shift from the UK’s Huawei ban just years prior.

The trip yielded approximately half a dozen signed agreements. The West Midlands, for example, secured a new UK headquarters in Birmingham for the Chinese energy company, EcoFlow.

But the visit’s significance extended beyond trade, according to East Midlands Deputy Mayor Nadine Peatfield. “There was a real hunger and appetite to rekindle those relationships,” she noted.

The trip evoked memories of the “golden era” of UK-China relations, a period characterized by close collaboration between then-Prime Minister David Cameron and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Those days seem distant. Political ties deteriorated under Boris Johnson, Rishi Sunak, and Liz Truss. Theresa May’s 2018 visit was the last by a UK prime minister.

This recent delegation, coupled with potential future visits by Sir Keir Starmer, suggests a turning point. But what are the broader implications?

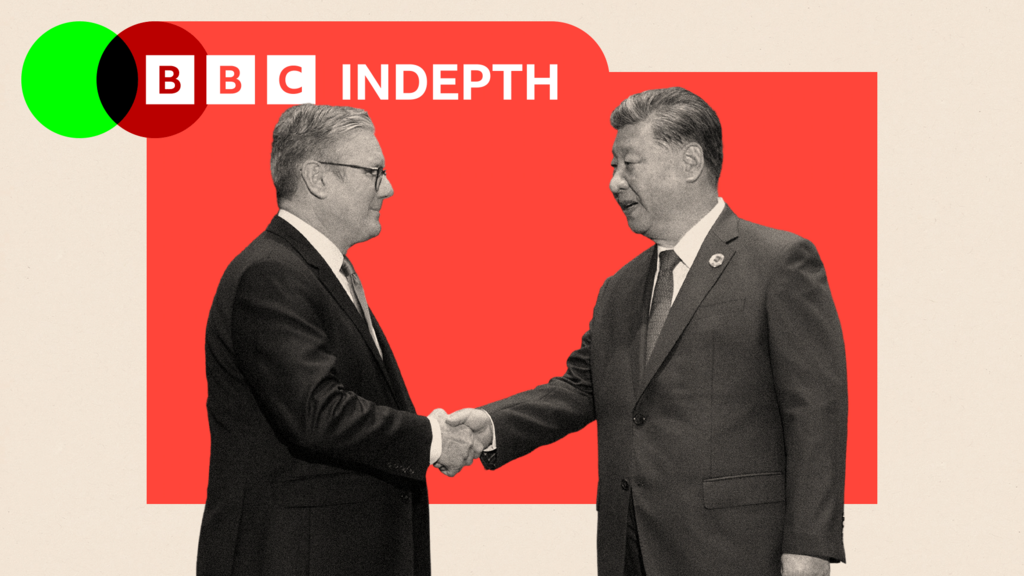

A shift began with a closed-door meeting between Sir Keir and President Xi in Brazil last November, signaling a renewed focus on climate and business cooperation.

Since then, Labour’s cautious approach has emphasized potential economic benefits.

In January, Chancellor Rachel Reeves co-chaired the first UK-China economic summit since 2019, stating, “Choosing not to engage with China is no choice at all.”

Reeves projected a £1bn boost to the UK economy, with £600m in agreements over five years, partly through reduced export barriers to China.

Following this, Energy Secretary Ed Miliband resumed climate talks, calling disengagement “negligence” given China’s role as the world’s largest emitter.

Labour characterizes its approach as “grown-up,” marking a departure from the past decade’s relationship.

The “golden era,” starting in 2010, prioritized economic opportunities, seemingly overshadowing human rights and security concerns.

However, by September 2023, Rishi Sunak highlighted China’s threat to “our open and democratic way of life.”

Labour’s manifesto promised a “long-term and strategic approach.”

China’s near-monopoly on rare earth minerals, crucial for high-tech and green industries, makes it vital to global supply chains.

“China’s influence will grow substantially, especially with the US turning inwards,” notes Dr William Matthews, a China specialist at Chatham House.

“The world will become more Chinese, necessitating sensible engagement.”

Andrew Cainey of the UK National Committee on China emphasizes the need for officials to see China firsthand post-pandemic.

Many believe direct contact is essential to assess both opportunities and challenges.

Opportunities are seen in economics, climate, and education. Professor Kerry Brown of King’s College London points to intellectual, technological, AI, and life sciences advancements.

Ignoring China would disregard its economic standing, but engagement carries risks, Dr Matthews cautions.

Charles Parton, a former diplomat, raises concerns about economic and national security.

He warns against Chinese access to the national grid, citing potential disruptions during times of tension.

The China Chamber of Commerce to the EU expressed concern over the “politicisation” of deals between European wind developers and Chinese turbine suppliers.

James Sullivan of Rusi highlights concerns about China’s increasingly strategic and politically focused activities in cyberspace.

The UK’s defence review labels China a “sophisticated and persistent challenge,” citing its technology’s proliferation as a key threat.

MI5 Director General Ken McCallum previously warned of a large-scale espionage campaign by China.

Professor Brown dismisses some espionage narratives as “fairytales,” while Beijing denies such accusations.

Sir Keir and his team will likely monitor Washington’s reaction.

Peter Navarro, a Trump advisor, labeled Britain “an all too compliant servant of Communist China,” urging against deeper ties.

Dr Yu Jie of Chatham House notes America’s significant influence on UK-China policy.

Analysts in both the UK and China agree on the need for dialogue, despite differing opinions on collaboration and avoidance areas.

These boundaries remain undefined, hindering effective engagement for businesses and officials.

“Firefighting individual issues without a systematic plan is unsustainable,” warns Mr. Cainey.

Challenges include Chinese investments, illustrated by the government’s April takeover of British Steel from Jingye, prompting reassessment of future Chinese investments.

China’s foreign ministry warned against linking investments with security concerns.

Following his meeting with Xi, Starmer stated the government’s approach would be “rooted in the national interests,” acknowledging disagreements on human rights, Taiwan, and Ukraine.

Releasing British citizen Jimmy Lai from a Hong Kong prison remains a priority.

Labour’s manifesto pledged to “cooperate where we can, compete where we need to, and challenge where we must.”

However, specifics are lacking. Mr. Parton notes the absence of a clear strategy from Number 10.

He advises a cautious approach, prioritizing national security even at potential short-term economic costs.

Labour anticipates clarity from the delayed China “audit,” due this month, but its effectiveness is doubted.

A Starmer visit to Beijing would indicate agreement on improving relations, Dr Yu suggests.

China skepticism persists in Westminster.

Even with a defined strategy, the UK’s China-related expertise remains a question.

Ruby Osman of the Tony Blair Institute advocates for enhancing UK capabilities holistically, diversifying engagement points.

This would allow the UK to engage more effectively with China, regardless of the perceived security or economic implications.

Top image credit: PA

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Sign up for our Politics Essential newsletter to keep up with the inner workings of Westminster and beyond.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has announced plans to free up land at Moorside for a power plant.

Rachel Reeves’ spending review will have a huge impact the Welsh government’s budget.

The future for EVs will inevitably involve China. But where does that leave the UK and Europe markets – and what of the questions around national security?

Some Labour MPs are using the move to renew their calls for planned benefit cuts to be reversed.

Voters feel change in the air in a Labour heartland with a long history of political activism.