Irvine Welsh gestures towards the second story of a weathered stone building in Leith, Edinburgh’s historic port area.

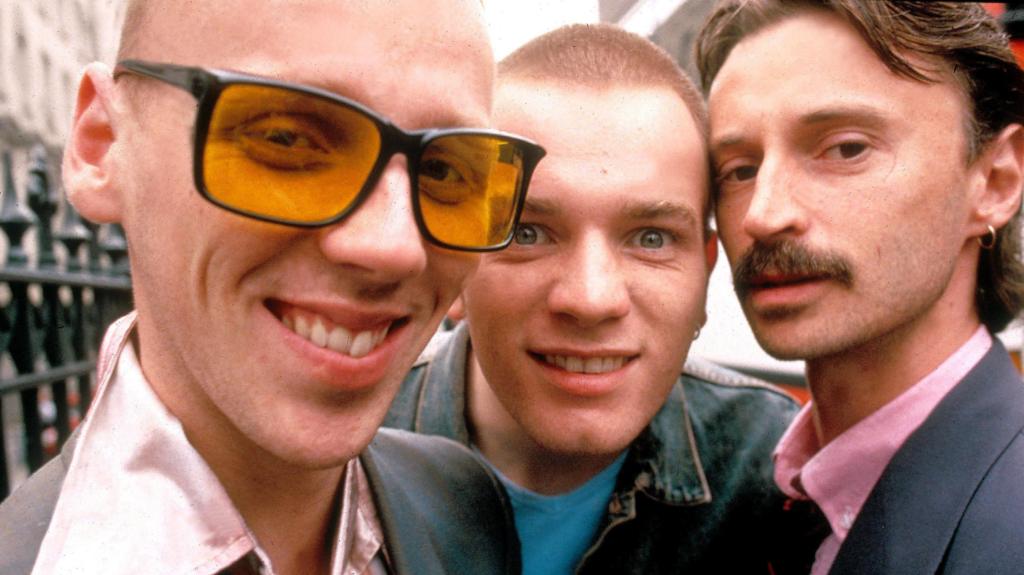

Ahead of the release of his sequel to the seminal 1993 novel, Trainspotting, the celebrated author points out the window, overlooking a local park, where he penned his breakthrough work—a novel later adapted into a critically acclaimed film starring Ewan McGregor and Jonny Lee Miller.

Welsh, the son of a Leith docker and a waitress, a former electrical engineering student, punk musician, and recovering heroin addict, had returned to his Leith roots from London and “just started typing.” He reveals that prior to writing Trainspotting, he resolved, “this is my last chance to do something creative.”

Trainspotting vividly portrays the lives of heroin-addicted friends in Edinburgh. Marked by violence, dark humor, and often shocking events, the book captures the social degradation stemming from the decline of Britain’s industrial heartland. Welsh’s debut novel, it went on to sell over a million copies in the UK alone.

However, as he wrote in the early ’90s, he was unaware of the success that awaited. “I just wanted to get it done,” he states. The effort undeniably paid off.

The book and film resonated so powerfully with the cultural zeitgeist that, more than three decades later, official Trainspotting tours are still available in Leith. On a brisk Scottish summer day, however, I am receiving a personalized tour from the author himself, visiting some of the pivotal locations that inspired his writing.

We visit the distinctive “Banana Flats,” formally known as Cables Wynd House, which dominates the Leith skyline and where his character Sick Boy (portrayed by Miller in the film) grew up.

We also stop by the Leith Dockers’ Club, where Renton (played by McGregor) accompanies his parents and where Welsh recalls spending time “as a kid, sitting there with lemonade and crisps” and “feeling really sort of resentful” while others indulged in alcohol.

Welsh’s latest work, Men in Love, revisits his iconic characters. While he has previously written follow-up books and a prequel about the Trainspotting crew, this novel picks up immediately after the first one concludes, with Renton fleeing with the proceeds from a major drug deal.

This time, Welsh explores the experiences of young men as they fall in love and navigate relationships. He explains that he was partly motivated to write it because “we’re living in a world that seems to be so full of hate and poison… I think that it’s time we focused more on love as a kind of antidote to all that.”

Readers should not anticipate saccharine romances, however, as this is, after all, a work by Welsh. The cheating, lying, manipulative, and occasionally horrifying behavior of some characters remains prominent.

The book even includes a disclaimer stating that, because the novel is set in the 1980s, many characters “express themselves in ways that we now consider offensive and discriminatory.”

Welsh indicates that the publishers insisted on the disclaimer. “They felt we live in such sensitive times that we need to make that point.”

“We live in a much more censorious environment,” he continues. While he acknowledges that misogynistic terms in the book, such as “fat lassie,” are hurtful and “there’s a good reason why we don’t say them,” he fears that state-imposed restrictions on speech could lead down “a dangerous road.”

Men in Love extends into the early ’90s. It is being released amid a wave of ’90s nostalgia in Britain, with Oasis on tour and Pulp’s surprise Glastonbury set receiving widespread acclaim.

Welsh says he “never left” that era, but notes that younger generations also feel nostalgic for it because “people had lives then.”

He partly attributes cultural changes to the internet and social media, which he believes has become “a controlling rather than an enabling force.”

Drawing on his understanding of addiction, Welsh hopes for “more judicious” use of social media in the future, pointing to the prevalence of people “with their phones stuck to their face” while in public.

“If we survive the next 50 years, that’s going to look as strange in film as people chain smoking cigarettes did back in the 80s.”

He also believes the internet is contributing to a decline in intelligence. “When you get machines thinking for you, your brain just atrophies.” He worries we are heading towards “a post-democratic, post-art, post-culture society where we’ve got artificial intelligence on one side and we’ve a kind of natural stupidity on the other side, we just become these dumbed-down machines that are taking instructions.”

The success of Trainspotting, he suggests, stemmed in part from a time when people were more open to reading challenging and unconventional books. As the money flowed in, it afforded him the freedom to write.

He is also a DJ and is releasing an album with the Sci-Fi Soul Orchestra to accompany his new book. The disco tracks relate to the characters, storyline, and “emotional landscape” of the novel.

Music is “fundamental” to his writing, and he is always “looking for that four-four beat all the time while I’m typing.”

He develops a playlist in his mind for each character and theme.

Renton is into Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, and Velvet Underground, while Sick Boy also enjoys Marvin Gaye, Bob Dylan, and New Order, he explains.

The aggressive and violent Begbie, on the other hand, likes “Rod Stewart and power ballads basically.”

When asked about a recent comment from Rod Stewart suggesting the public should give Reform UK leader Nigel Farage a chance, I wondered if Irvine Welsh believes his Trainspotting characters would support that party if they were growing up now.

He rejects the notion, asserting that the Scottish working classes “still have a radical kind of spirit. They’re not really there to be the stooge of some public school idiot.”

Although he later adds, “people are so desperate that they’ll go along with anybody who has that rhetoric of change.”

Welsh has always been politically engaged, and as we walk around the area where he grew up, he describes how Margaret Thatcher “at a stroke” ended centuries of shipbuilding in Leith. Five thousand dockers became none, he says.

Trainspotting also resonated, he believes, because it “heralded the adjustment to people living in a world without paid work. And now we’re all in that position.”

He argues that Britain’s class system is changing “because of this massive concentration of wealth towards the wealthy.”

While the working classes already have no money, the middle classes are increasingly burdened by debt and less able to pass on their assets, creating increased insecurity.

“We’re all members of the Precariat, basically. We don’t know how long we’ll have paid work if we do have it, and we just don’t know how long this will last because our economy, our society is in a long-form revolutionary transformation.”

During my time with Welsh, I have not only toured Leith but also gained insight into his mind, which is overflowing with opinions on everything from our dystopian future to why the best music was made in the analogue era, and even his response to a hypothetical knighthood offer (a firm no, incidentally).

As our time concludes, he heads into the bar at the Dockers’ Club to meet a friend he first met in primary school 60 years ago. His longtime friend jokes that he is a plumber while Welsh is a millionaire author. The affection between them is evident.

Trainspotting may have fundamentally altered Welsh’s life, but he remains deeply connected to the community that shaped him and the Leith he so vividly transformed into fiction.

Men in Love is published on 24 July 2025

Political strategist Chris Bruni-Lowe claims in a new book that eight words hold the key to electoral success.

The author posted a lengthy statement challenging claims made in the Observer newspaper at the weekend.

Raynor Winn has defended herself against accusations she gave misleading information in the 2018 book.

Three hundred years since they first appeared, the capital’s traditional members-only clubs have endured and evolved. Now a new book explores this peculiarly British phenomenon.

Writer Raynor Winn denies allegations that some elements of her best-selling book misled readers.