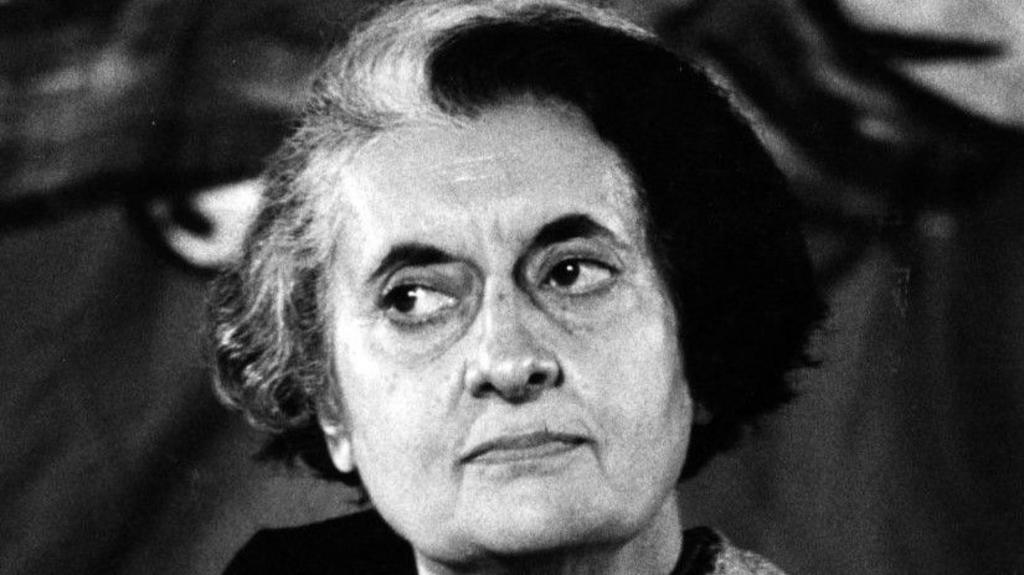

During the 1975 Indian Emergency, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government secretly explored a significant constitutional shift away from parliamentary democracy, according to historian Srinath Raghavan’s new book, Indira Gandhi and the Years That Transformed India.

While suppressing political opposition and civil liberties, Gandhi’s administration, guided by top bureaucrats and party loyalists, initiated plans for a presidential system. This model, partly inspired by Charles de Gaulle’s France, aimed to centralize executive power, diminish the judiciary’s influence, and reduce parliament’s role.

The initiative began in September 1975 when B.K. Nehru, a close Gandhi aide, advocated for a directly-elected president empowered to make difficult decisions without parliamentary constraints. Nehru envisioned a seven-year term, proportional representation, a weakened judiciary, and stricter press regulations, even suggesting the non-justiciability of fundamental rights.

This proposal, enthusiastically received by senior Congress leaders like Jagjivan Ram and Swaran Singh, was presented to Gandhi, who, while not publicly endorsing it, authorized further exploration. A confidential document, “A Fresh Look at Our Constitution,” proposed a president with powers exceeding even those of the American counterpart, including control over judicial appointments and legislation.

Although the presidential system plan never materialized formally, its influence is evident in the 1976 Forty-second Amendment Act. This act expanded parliamentary power, limited judicial review, and further centralized executive authority, making it harder to strike down laws and diluting the constitution’s ‘basic structure doctrine’. It also granted the federal government extensive powers regarding the deployment of armed forces and the imposition of President’s Rule.

While not a full presidential system, the amendment reflected its core tenets: a powerful executive, a marginalized judiciary, and weakened checks and balances. The Statesman newspaper criticized the amendment for shifting the constitutional balance in favor of parliament.

Despite calls for a constituent assembly and even lifelong power for Gandhi, she ultimately steered the amendment through parliament. Following her 1977 electoral defeat, the Janata Party partly reversed these changes through the Forty-third and Forty-fourth Amendments.

Remarkably, the idea resurfaced in 1982, with Gandhi herself considering a presidential bid. However, she ultimately appointed Zail Singh as president instead. According to Prof. Raghavan, the Emergency-era push stemmed from a desire to consolidate power, not a long-term constitutional vision. The enduring legacy, he suggests, was largely unintended.

While the presidential system idea persisted within Congress, including a 1984 proposal by Vasant Sathe, Indira Gandhi’s assassination brought a definitive end to the discussion. India remained a parliamentary democracy.

Violence erupted in parts of the state after the arrest of leaders from the Arambai Tenggol rebel group.

The paintings are set to go up for auction for the first time on 12 June in India’s financial capital, Mumbai.

A now-demolished guest house in Mecca is at the centre of a bitter family tussle in India.

Relations had deteriorated after accusations India was behind the murder of a Sikh activist in Canada.

Priya Rastogi and her family depend on her late husband’s work visa which expires in August.