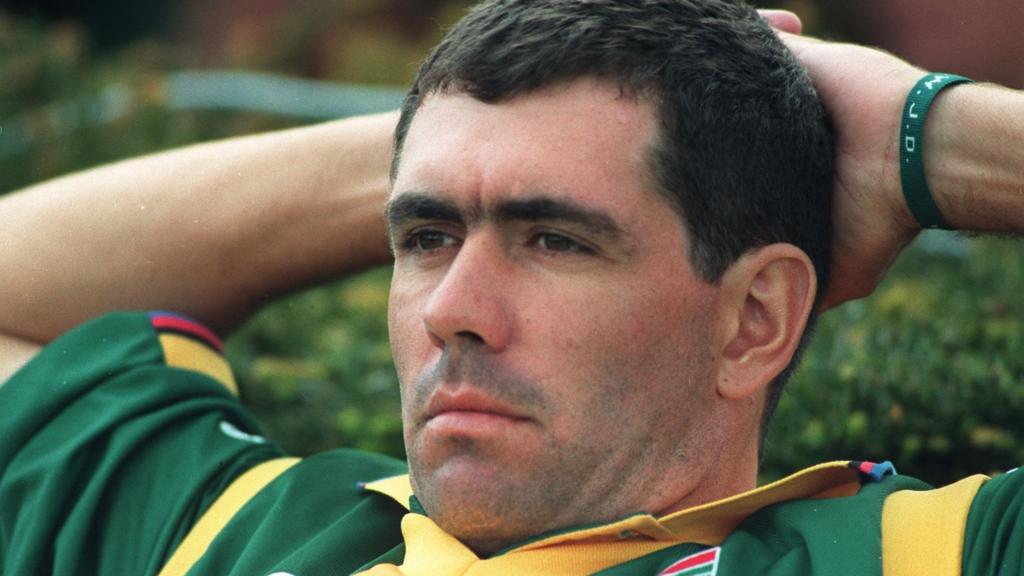

Hansie Cronje, match-fixing and the plane crash that left behind a complex legacy

Within the wood-paneled confines of an Edwardian edifice in Cape Town, the devastated figure of Hansie Cronje lay prostrate.

Away from the intrusive lenses of cameras and the voracious media, deep within the Centre of the Book in the city’s legal district, the former South Africa cricket captain, overcome with emotion and dressed in a charcoal suit, had collapsed in tears.

His father, Ewie, and brother, Frans, endeavored to console him. Cronje had just testified before the King Commission, the inquiry tasked with investigating allegations of match-fixing in cricket, at the heart of which he was.

Barely two years later, Ewie and Frans would serve as pallbearers at Hansie’s funeral, following his untimely death in a plane crash.

It has now been a quarter-century since Cronje’s life was irrevocably altered, and cricket plunged into crisis, by a scandal that reverberated throughout the sport.

Cronje’s story, revisited in Sport’s Strangest Crimes on BBC Sounds, remains a perplexing enigma.

This video can not be played

Moment South Africa great Allan Donald learns of team-mate’s match-fixing confession

Wessel Johannes ‘Hansie’ Cronje was born in Bloemfontein, into a family steeped in sports and devout Christianity.

Cronje received his education at the esteemed Grey College, where he served as head boy, captained both the rugby and cricket teams, and was marked for future success.

Former South Africa fast bowler Allan Donald, a childhood friend of Cronje’s who attended the Technical High School in the same city, recalled that even as a teenager, Hansie was a “deep thinker” who possessed “leadership qualities in every aspect of his being”.

Cronje was appointed captain of Orange Free State at the age of 21, and the batting all-rounder soon became an integral part of the post-apartheid South Africa team that re-emerged onto the international stage.

He was entrusted with the captaincy of the Proteas in 1994, and his astute strategies and composed demeanor lent him a statesmanlike presence as he transformed the team into a formidable international contender.

Cronje also cultivated a close personal relationship with President Nelson Mandela.

During a period when Afrikaner politicians began to recede from prominence, Cronje was among those from that community who stepped into the void.

Mandela lauded Cronje in 1996 for the “excellent manner” in which he “led the national team” at a time when “sport had played a role in uniting our country”.

Cronje was a figure who transcended the realm of cricket.

Former England batter Mark Butcher recalled that Cronje was “incredibly personable, very charismatic, quite humble, and possessed a sense of humor” off the field.

However, there was a darker aspect to Cronje, particularly when it came to financial matters.

Good-looking and remarkably approachable, Cronje was a sponsor’s dream, and endorsements flowed freely. Yet, Donald noted that Cronje was “tight-fisted” when it came to simple gestures like buying post-match beverages.

Cronje’s frugality extended beyond merely avoiding his turn to buy a round. It bordered on the obsessive.

He would receive complimentary clothing and equipment as part of a sponsorship agreement with Puma but would sell any unused items to younger players rather than giving them away.

During a stint playing for Leicestershire, he took his wife Bertha on a romantic getaway to Paris, but his sister revealed that the couple subsisted “on bread and water” as Hansie balked at the prices in the French capital.

Hansie Cronje and Nelson Mandela maintained a close relationship

This video can not be played

‘$20k’ to score under 20 runs?

That affinity for money also made Cronje one of the most accessible cricket captains around, and he was frequently visited by individuals, especially while touring in South Asia.

The rest of the South Africa squad would roll their eyes as yet another stranger arrived for a meeting with him.

This led to dealings with unscrupulous characters, particularly those involved in betting, and there was an early indication of what was to come in 1996.

Prior to a one-off ODI between South Africa and India, appended to the end of a Test tour as a benefit match for Mohinder Amarnath, Cronje convened a meeting in their Mumbai hotel for the players to consider an offer of $250,000 to deliberately lose the match.

The offer was rejected, but it demonstrated the security Cronje felt in his position.

“Bringing it up in a team meeting was indicative of the power and untouchability that he felt,” observed South African journalist Neil Manthorp.

Fast forward to Nagpur in 2000, Cronje attempted to coerce South Africa batter Herschelle Gibbs and seam bowler Henry Williams into spot-fixing offenses.

Both men agreed but subsequently did not carry out the instructions.

“I always found it a struggle to actually say ‘no’ to him, you know?” reflected Gibbs.

“He was regarded in such high esteem and respected so much, and I never once thought of the consequences.”

Both Gibbs and Williams were non-white players, but suggestions that it was racially motivated are dismissed by those who knew Cronje.

Still, how was Cronje able to manipulate his team-mates with such ease? Manthorp said he was on an “elevated platform” and “very few people were prepared to stand up to him”.

“Hansie had quite a temper. He’d become, I think, accustomed to not being questioned,” he added.

The most infamous of Cronje’s dealings with bookmakers occurred during the rain-affected fifth Test between South Africa and England at Centurion Park in early 2000.

With the Proteas recommencing their first innings on the fifth day, Cronje, prompted by a bookie named Marlon Aronstam, contrived an unprecedented innings forfeiture for both sides to ensure a result.

England captain Nasser Hussain later compared his agreement with Cronje over what target his side would chase to the haggle scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, with Cronje immediately accepting the figure Hussain proposed.

Cronje’s innovative action to create a result on what would have otherwise been a dead final day of a Test largely drew praise, even if it did not quite sit right with everyone.

“After the initial celebrations I realized I did not experience the usual euphoria that would follow a Test win,” said Butcher.

“Almost instantly I knew why – it didn’t feel we’d earned it.”

Michael Holding, covering the match for Sky Sports, received “tons of phone calls and letters” over something he said on air during a commentary stint, having sensed foul play.

“I said if this game was being played on the Indian subcontinent, people would start talking about bookmakers,” Holding said.

“I just knew something was going on and that was my total focus. I was basically disgusted at what I was watching.”

This video can not be played

Beers with the opposition captain mid-series?

When Delhi police released transcripts of recorded conversations between Cronje and Indian bookmaker Sanjeev Chawlar in early April 2000, it was met with denials from the man himself and South African cricket officials, as well as widespread disbelief.

Cronje was initially identified in the calls by a twist of fate.

Pradeep Srivastava, the deputy commissioner of Delhi’s crime department, had been working on extortion cases and taken some tapes home with him.

One of Srivastava’s children had listened to a wire-tap cassette, left in the home hi-fi system, and asked his father why he had a recording of Cronje’s voice.

Srivastava’s son had watched a post-match interview with Cronje on Indian television the previous day and recognized his voice.

With the net closing, Cronje confessed.

At 3am on 11 April 2000, he admitted his guilt to Rory Steyn, a South African security consultant working for the Australia cricket team, in a Durban hotel where the pair were staying.

“I walked into his suite and all the lights were on,” Steyn remembered.

“He had a handwritten document and said ‘you may have guessed, but some of the stuff that is being said against me is actually true’.”

A couple of months later, Cronje attended the King Commission, where he was offered immunity from prosecution in exchange for full disclosure.

During three days of cross-examinations, broadcast on television and radio, which captivated South Africa and the cricket world, Cronje gave his side of the story.

Or at least some of it, given the input of his own lawyers.

He admitted to taking large sums of money, as well as accepting a leather jacket for his wife Bertha, in exchange for providing information to bookmakers and asking his team-mates to underperform.

But he claimed that South Africa had never “thrown” or “fixed” a match under his captaincy.

“To my wife, family, and team-mates, in particular, I apologise,” he said during a rather robotic reading of an opening statement lasting 45 minutes.

Cronje was banned from cricket for life, unsuccessfully challenging the suspension.

Further investigations into the veracity of Cronje’s testimony during the inquiry were halted when he died in a plane crash in June 2002.

Cronje had boarded a small cargo aircraft in Johannesburg, which crashed in mountainous terrain amid adverse weather conditions while attempting to land at George airport.

Cronje, then working as an account manager for a manufacturer of heavy-duty construction equipment, was flying back to see his wife at their home near Fancourt Estate, a luxury golf resort.

His death was attributed to weather, pilot error, and possible instrument failure, but nevertheless prompted conspiracy theories.

Former Nottinghamshire captain Clive Rice, who played three ODIs for South Africa, called Cronje’s death “very fishy” and linked it to the subsequent death of Bob Woolmer, the former South Africa coach who was in charge of Pakistan when he died.

“Certain people needed him [Cronje] out. Whether it was one, two, or 15 people that were going to die it didn’t matter,” said Rice, who passed away in 2015.

“Hansie was the one that was going to have to go and if they could cover it up as a plane crash then that was fine.”

Eerily, Cronje himself had predicted in speeches and written in a magazine about the potential to “die in a plane crash” because of the “constant travel by air”.

Ed Hawkins, a specialist betting investigative journalist, dismissed the notion that bookmakers were somehow behind the incident.

“I’ve never found any information basically worth my time or effort to launch a full-scale investigation,” Hawkins said.

Steyn, the security consultant, called it “ludicrous” to suggest there was a “conspiracy to murder him by bringing the plane down”.

The Hansie Cronje saga and its fallout gripped the whole of South Africa

Cronje’s ashes were placed in a memorial at his beloved Grey College.

A generation has now passed since the former South Africa captain’s murky involvement with bookmakers came to light, but his legacy remains complex.

His death at the age of 32 meant he was denied an opportunity for redemption within a sport he felt so deeply connected to.

For some, Cronje had been vulnerable, and had the anti-corruption measures that came in the wake of his fall from grace been in place, his story might have unfolded differently.

“In a moment of stupidity and weakness,” Cronje himself said, “I allowed Satan to dictate terms to me rather than the Lord.”

Those close to him felt that once the depression following the King Commission lifted, Cronje’s life path had shifted for the better.

Cronje’s brother Frans produced a film based on Hansie in 2008, portraying the former South Africa skipper in a sympathetic light.

In the film, there’s a scene where a young black boy who had earlier torn a poster of Hansie off his wall is seen piecing it back together.

It was a metaphor for the national psyche which, post-apartheid, makes it “a lot easier for people to forgive” in South Africa, according to Frans.

Yet sports scientist Professor Tim Noakes, who worked with the South African team in the Nineties, went as far as to call Cronje a “psychopath”.

“He fitted the characteristics and it’s no remorse, no conscience,” he said.

“I understand that you can’t make the diagnosis without having properly examined people, but I just saw enough evidence for it in this man.”

The currency Cronje should have been remembered for was the number of runs he scored as an inspirational captain, rather than deposits in bank accounts in his name in the Cayman Islands.

“I don’t think he was evil. I think that’s far, far too strong a word,” said Manthorp.

“I do think that he was a skillful manipulator. I think that he was acutely aware of the power and influence that he had.”

For those outside the country, especially in a sport like cricket with its expected moral compass, it is perhaps even more difficult to separate the man from the crimes.

“I think that Hansie is a villain in this story,” Butcher added. “He might not be the villain, but he’s certainly a villain.”

The full six-part series of ‘Sport’s Strangest Crimes – Hansie Cronje: Fall From Grace’ is available on BBC Sounds.

Get cricket news sent straight to your phone