Once imposing statues of rams and lions graced the gardens of Sudan’s National Museum—priceless relics from the era when Nubian monarchs extended their domain into present-day Egypt. The museum also preserved intricate Christian wall paintings dating back centuries.

Typically, the museum drew awe-struck groups of schoolchildren, intrigued tourists eager to explore Khartoum’s highlights, and crowds for occasional performances in its grounds.

But that tranquillity was shattered two years ago when conflict erupted.

As Sudanese military forces reclaim control over Khartoum, following the expulsion of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the devastating impact of two years of warfare is starkly evident.

Key government buildings, banks, and office complexes now stand scorched and destroyed, with the museum—an emblem of Sudan’s cultural and historical richness—among the worst affected.

Senior officials report that tens of thousands of artefacts were either ruined or smuggled for sale during the RSF’s occupation of central Khartoum, where the museum is situated.

“They destroyed our identity and history,” Ikhlas Abdel Latif Ahmed, director of museums at Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums, told the BBC’s Newsday programme.

Prior to the turmoil, the National Museum was one of Sudan’s cultural treasures.

Located near the Presidential Palace at the convergence of the Blue and White Nile rivers, the institution chronicled successive civilisations that once flourished in the region.

Now, museum staff returning to assess the damage are confronted by shattered glass, spent bullet shells, and widespread evidence of looting.

“The building was genuinely unique and beautiful,” Ms Ahmed said.

“The militia”—the term used by Sudanese officials for the RSF—”took many outstanding artefacts and caused extensive destruction to the rest.”

Other museums and historic sites across Sudan have also suffered from looting. Last September, UNESCO warned of significant cultural threats and urged the art market to reject artefacts trafficked from Sudan.

At the outset of conflict, the National Museum was undergoing renovation, so many valuable items had been stored in boxes.

This may have inadvertently facilitated the removal of entire collections.

Authorities say invaluable pieces were taken to be illicitly sold abroad.

They suspect some valuables were transported by RSF members to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), though direct proof has not been provided. However, a UN panel has documented substantial RSF gold exports to the UAE even before the conflict began.

The UAE has faced repeated accusations of supporting the RSF financially, which all involved parties deny.

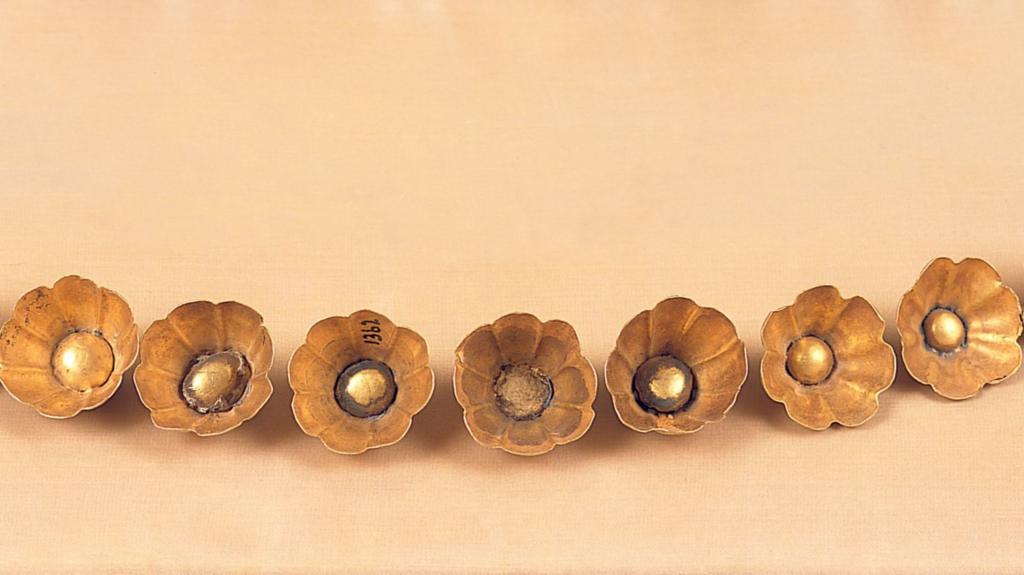

“We had a vault for the gold collection—they managed to breach it and take everything,” Ms Ahmed added.

“Whether they kept it or sold it, we do not know.”

The current location of treasures, including a gold collar from King Talakhamani’s pyramid at Nuri, dating to the 5th Century BC, remains unknown.

When asked about the artefacts’ estimated value, Ms Ahmed replied: “The museum’s collections are priceless—beyond any monetary estimation.”

Sudan’s transitional authorities say they will work with Interpol and UNESCO to seek the recovery of stolen objects from the National Museum and elsewhere.

Yet, regaining these artefacts is expected to be an extremely complex and perilous undertaking with no assurances of swift results.

The government and Sudanese commentators argue that the RSF’s attacks on museums, universities, and record offices are part of an intentional campaign to undermine the Sudanese state—an allegation the RSF rejects.

Amgad Farid, head of the Fikra for Studies and Development think tank, has been particularly outspoken about the cultural losses.

“The RSF’s actions surpass routine criminality,” he wrote in a statement by his organisation.

“They represent a targeted and malicious effort to sabotage Sudan’s historical legacy, erasing the heritage of Nubian, Coptic, and Islamic civilisations spanning more than 7,000 years—foundations of African and world history safeguarded in these museums.”

“This is not collateral damage of war—it is a systematic attempt to eradicate Sudan’s past, estrange its people from their roots, and exploit millennia of human history for gain.”

The fate of the National Museum—seized by armed groups, stripped of gold, its treasures plundered—reflects the hardships endured by countless Sudanese: displacement, loss of property, and theft of their possessions.

According to the United Nations, over 13 million people have been displaced and an estimated 150,000 killed since conflict erupted in 2023.

“This war is against the people of Sudan,” Ms Ahmed said, mourning both the profound human toll and irretrievable cultural losses.

Determined alongside like-minded colleagues, she remains committed to restoring the National Museum and other pillaged institutions.

“Inshallah [God willing], we will recover our collections,” she affirmed.

“And rebuild the museum even more beautiful than before.”

Visit BBCAfrica.com for more in-depth news from across the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica

Mac-Albert Hengari was taken into custody on Saturday after allegedly offering a bribe to persuade the woman to drop the complaint.

The BBC identifies security personnel involved in last year’s shooting of protesters outside Kenya’s parliament.

The ANC chairperson’s remarks follow months of US debate over race and land legislation.

The Vatican envoy to South Sudan urges that the Pope’s legacy be honoured through efforts toward peace.

A medical professional has sparked a national debate on the financial abuse experienced by some women who are primary earners.