India’s Election Commission recently released updated draft electoral rolls for Bihar, where crucial elections are scheduled for November, following a month-long revision of the voters’ list.

However, opposition parties and election watchdogs allege the process was rushed, with voters in Bihar reporting inaccuracies such as incorrect photos and the inclusion of deceased individuals in the draft rolls.

The Special Intensive Revision (SIR), conducted from June 25 to July 26, aimed to verify the details of the state’s 78.9 million registered voters. The commission stated that officials visited each voter, noting that the last such revision occurred in 2003, necessitating an update.

The new draft rolls list 72.4 million names, a reduction of 6.5 million. The commission attributes these deletions to 2.2 million deceased individuals, 700,000 duplicate registrations, and 3.6 million people who have migrated from the state.

Corrections are being accepted until September 1, with over 165,000 applications already received. A similar review is planned nationwide to verify nearly one billion voters.

Opposition parties have accused the commission of deliberately removing voters, particularly Muslims, who constitute a significant portion of the population in four border districts, to benefit Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the upcoming state election.

Both the Election Commission and the BJP have denied these allegations. In response to inquiries, the Election Commission provided its June 24 order on conducting the SIR and a July 27 press release outlining efforts to ensure no eligible voter was “left behind.”

“Furthermore, [the commission] does not take any responsibility for any other misinformation or unsubstantiated allegations being floated around by some vested interests,” it added.

The commission has not released a list of deleted names or a breakdown by religion, making it impossible to independently verify the opposition’s claims.

A report by the Hindustan Times newspaper indicated high voter deletions in Kishanganj, a district with a significant Muslim population, but not in other Muslim-dominated constituencies.

Parliamentary proceedings have been repeatedly disrupted as opposition MPs demand a debate on what they consider a threat to democracy, chanting slogans such as “Down down Modi,” “Take SIR back,” and “Stop stealing votes.” The Supreme Court is also reviewing the matter following a challenge by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), which questioned the timing of the revision.

“It comes just three months before the assembly elections, and there has not been enough time given to the exercise,” Jagdeep Chhokar of ADR told the BBC.

“As reports from the ground showed, there were irregularities when the exercise was being conducted, and the process of data collection was massively faulty,” he added.

The ADR has argued in court that the exercise “will disenfranchise millions of genuine voters” in a state that is one of India’s poorest and home to “a large number of marginalised communities.”

It contends that the SIR shifts the burden onto individuals to prove their citizenship, often requiring documentation for themselves and their parents within a limited timeframe, an insurmountable task for many poor migrant workers.

While the draft roll was being published, we visited Patna and nearby villages to gauge voters’ opinions on the SIR.

In Danara village, home to the Mahadalits, one of the poorest communities, most residents work on farms owned by upper-caste individuals or are unemployed.

The homes are dilapidated, open drains run alongside narrow lanes, and a stagnant puddle near the local temple has become brackish.

Most residents had little to no awareness of the SIR or its implications, and many were unsure if officials had even visited their homes.

However, they deeply value their right to vote. “Losing it would be devastating,” says Rekha Devi. “It will push us further into poverty.”

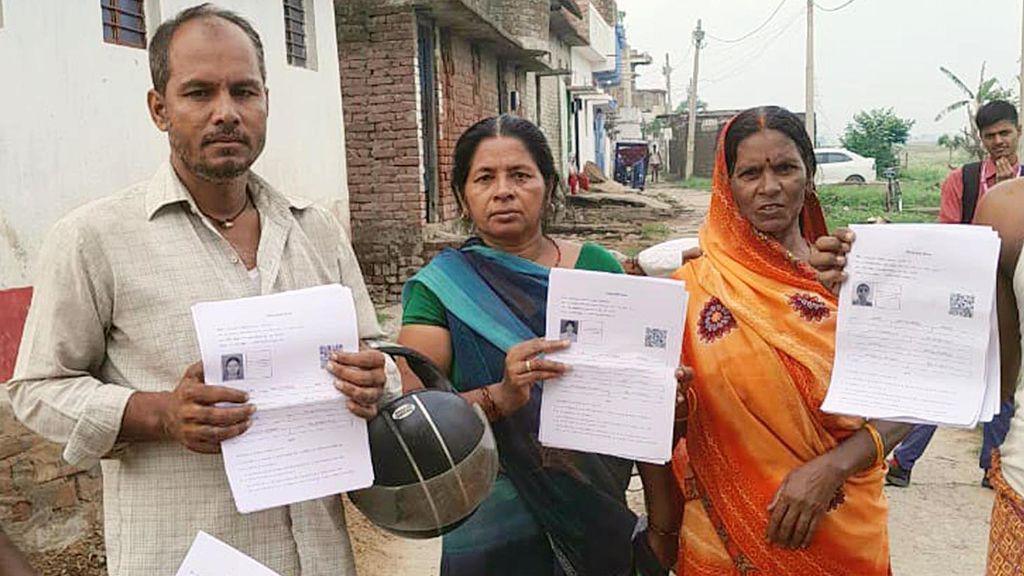

In Kharika village, many men said they had heard of the SIR and submitted forms, spending 300 rupees (£3.42; $4.25) on new photographs. However, after the draft rolls were released, farmer and retired teacher Tarkeshwar Singh described them as “a mess.” He showed pages with his family’s details, pointing out errors, including the wrong photo next to his name.

“I have no idea whose photo it is,” he says, adding that his wife, Suryakala Devi, and son, Rajeev, also have incorrect pictures. “But the worst is my other son Ajeev’s case – it has an unknown woman’s photo.”

Mr. Singh further listed other inconsistencies: in his daughter-in-law Juhi Kumari’s document, he is listed as her husband instead of his son. Another daughter-in-law, Sangeeta Singh, is listed twice from the same address, with only one entry containing her correct photo and date of birth.

He stated that many of his relatives and neighbors have similar complaints, pointing to a cousin who died more than five years ago but is still on the list, and at least two names that appear twice.

“There’s obviously been no checking. The list has dead people and duplicates and many who did not even fill the form. This is a misuse of government machinery and billions of rupees that have been spent on this exercise.”

Mr. Chhokar of ADR said they will raise these issues in the Supreme Court this week. In July, the court said it would consider staying the exercise if petitioners could produce 15 genuine voters missing from the draft rolls.

“But how do we do that since the commission has not provided a list of the 6.5 million names that have been removed?” he asks.

Mr. Chhokar added that one justice on the two-judge bench suggested delinking the exercise from the upcoming elections to allow more time for a proper review.

“I’ll be happy with that takeaway,” he said.

The SIR and draft rolls have divided Bihar’s political parties: the opposition Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) questions them, while the ruling Janata Dal (United)-BJP alliance supports them.

“The complexity of this revision has left many people confused,” said Shivanand Tiwari, general secretary of the RJD.

Tiwari questioned the Election Commission’s “claims that 98.3% electors have filled their forms” and stated that “in most villages, our voters and workers say the Block Level Officer (BLO) – generally a local schoolteacher appointed by the commission to go door-to-door – did not visit them. Many BLOs are not trained and don’t know how to upload forms.” (The commission has asserted that the BLOs have worked “very responsibly.”)

Tiwari alleges that the “commission is partisan and this is manipulation of elections.”

“We believe the target are border areas where a lot of Muslims live who never vote for the BJP,” he said.

The BJP and the JD(U) have rejected the criticism, calling it “entirely political.”

“Only Indian citizens have the right to vote, and we believe that a lot of Rohingya and Bangladeshis have settled in the border areas in recent years. And they have to be weeded out from the list,” said Bhim Singh, a BJP MP from Bihar.

“The SIR has nothing to do with anyone’s religion, and the opposition is raising it because they know they will lose the upcoming election and need a scapegoat to blame for their loss,” he added.

JD(U)’s chief spokesperson and state legislator Neeraj Kumar Singh said “the Election Commission is only doing its job.”

“There are lots of voters on the list who figure twice or even three times. So shouldn’t that be corrected?” he asked.

Weeks after Sunjay Kapur’s death, the question of succession has become the subject of media speculation.

Veer Singh and Kali Devi were away buying groceries when flash floods hit their village on Tuesday.

An upscale Indian suburb is rounding up some of its most marginalised residents, saying they are illegal immigrants.

Experts say the US’s sweeping tariffs will slow down the Indian economy if Delhi fails to secure a deal.

Campaigners warn the move will not close all the recycling loopholes being exploited by criminals.