Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, once lauded as a reformist leader, has defied expectations throughout his 32-year rule.

He primarily resides at a rural retreat 20km outside Asmara, the capital. Power flows solely through him, as cabinet meetings have ceased since 2018. He receives a constant stream of officials and dignitaries at his secluded residence, where ordinary Eritreans also seek – often in vain – his assistance.

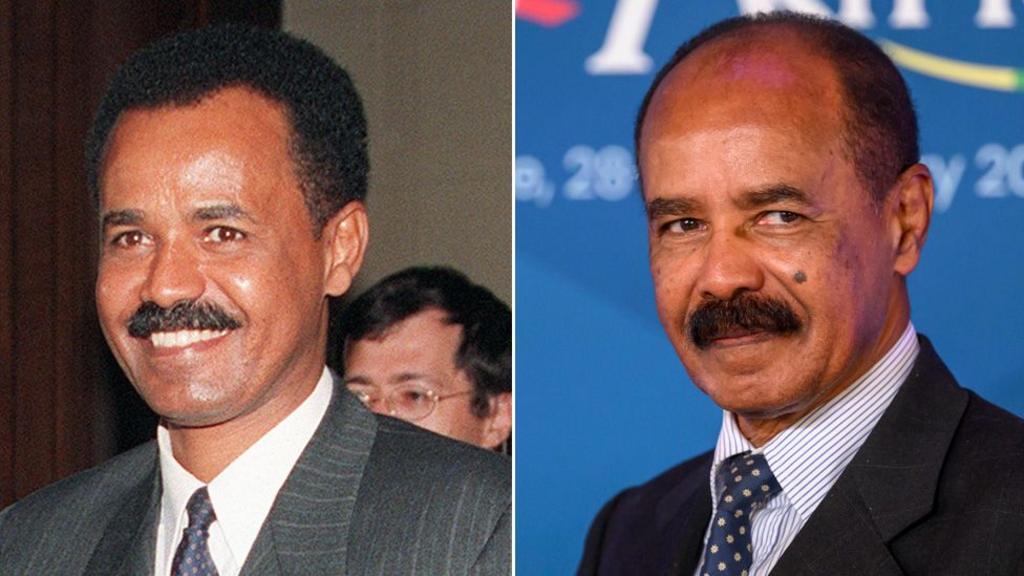

At 79, Afwerki has never faced an election, with no prospect of change on the horizon. However, the 1990s presented a starkly different picture.

In 1991, the then 45-year-old Afwerki, leading the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), defeated Ethiopia. His charisma inspired hope domestically and internationally.

His 1993 debut on the world stage in Cairo saw him criticize older African leaders clinging to power, promising Eritrea a different path – a democratic order to underpin development. This stance earned widespread praise.

The early post-independence years brought positive international relations. President Bill Clinton, after meeting Afwerki in 1995, commended Eritrea’s democratic progress as a new constitution was drafted.

Afwerki, initially a “transitional president,” was expected to step down after elections following the constitution’s ratification in 1997. However, the 1998 Eritrean-Ethiopian border war provided a pretext for indefinite postponement.

Even after a 2000 peace agreement, his commitment to multiparty democracy was tested. Several cabinet ministers, including former allies, called for reforms.

In 2001, the “G-15,” a group of senior officials, openly accused Afwerki of autocracy, demanding constitutional implementation and elections. This followed a period of relative openness, with critical newspapers emerging.

The path toward democratization was abruptly halted in September 2001. Independent newspapers were shut down, journalists detained, and 11 G-15 members, including former ministers, arrested – their fate unknown.

Afwerki, rejecting the democratic process as a “mess,” declared the ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) not a party, but “a nation,” ending any hope of reform.

This earned Eritrea international condemnation, although supporters praise Afwerki for national liberation and resistance to Western influence. He dissolved the transitional assembly in 2002 and the cabinet in 2018.

Abdella Adem, a former official now in exile, attributes Afwerki’s repression to an inherent obsession with power, citing the systematic removal of potential rivals within the EPLF.

A 2014 proposal for a new constitution, following a 2013 coup attempt, remains unfulfilled. The coup, aiming to restore the 1997 constitution and release prisoners, was swiftly suppressed.

Zeraslasie Shiker, a former diplomat in exile, highlights the connection between imprisonment and the erosion of democratic institutions. International isolation led to Afwerki’s withdrawal from global forums.

Eritrea’s economy struggles, hampered by infrastructure limitations and state control, according to the World Bank. Afwerki acknowledges economic problems but rejects humanitarian aid, prioritizing self-reliance.

For many Eritreans, particularly those trapped in indefinite national service, life under Afwerki’s rule is harsh, leading to mass exodus. Hundreds of thousands have sought refuge abroad.

Afwerki’s recent independence day speech offered no reforms, no mention of elections or prisoner releases, and no economic recovery plan. Despite widespread criticism, he retains support among certain segments of the population and some within the diaspora.

Since 2014, he has resided at his rural home, and a reported attempt to groom his son as a successor failed in 2018. With no clear succession plan or credible opposition, a post-Afwerki Eritrea remains uncertain.

While some see his recent Easter church attendance as a sign of potential change, for now, Afwerki’s grip on power remains firm, leaving Eritreans in a prolonged state of anxious anticipation.

Go to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica