A grieving father gestures towards two bullet holes marring his home’s wall, a grim testament to a tragedy that irrevocably altered his family’s life.

This poignant scene encapsulates the devastating impact of gang violence.

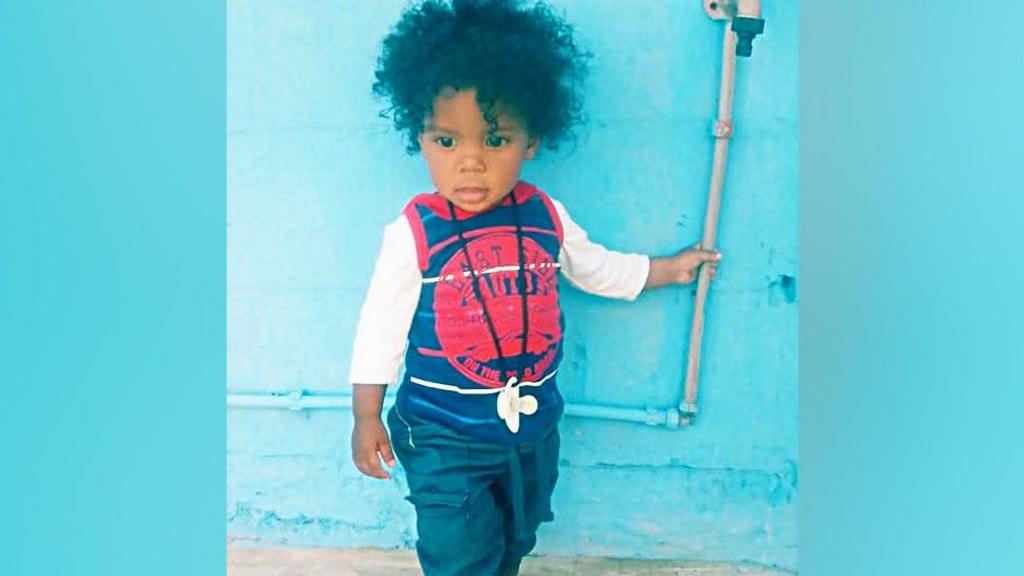

Devon Africa’s four-year-old son, Davin, was fatally shot in February, an innocent casualty of a shootout between rival gangs.

He is one among many victims of the pervasive gang warfare plaguing Cape Town’s Cape Flats townships—a lingering consequence of apartheid’s forced relocation of non-white populations to under-resourced peripheries.

“This bullet hole,” he explains, solemnly indicating the wall, “is where he slept.”

The family has already endured unimaginable loss.

Davin’s older sister, Kelly Amber, was also murdered two years prior, a victim of gang crossfire at the age of 12.

Devon and his wife, Undean, are left with only their youngest daughter.

“She asks, ‘Where’s my brother?'” Undean shares, her voice heavy with grief. “We tell her he’s with Jesus, in our hearts.”

Their tragedy is mirrored across Wesbank and the broader Cape Flats, despite police assurances of increased patrols.

Statistics paint a stark picture. The Western Cape, home to the Cape Flats, consistently reports the highest number of gang-related murders in South Africa, according to official police data.

While officially designated a government priority, President Cyril Ramaphosa’s initiatives—a special unit formed in 2018 and a brief army deployment the following year—have failed to stem the persistent violence.

“Generations have been born into these gangs,” observes Gareth Newham, head of the Justice and Violence Prevention program at the Institute for Security Studies. “They thrive in neglected areas, filling the void left by the state. They provide necessities—food, utilities, transportation, even funeral expenses and school fees.”

Deeply embedded within the community, their operations make law enforcement efforts exceedingly difficult, enabling them to utilize non-gang members’ homes to store contraband.

However, dedicated individuals are actively combating this issue.

Fifteen kilometers from Wesbank, in Hanover Park, Pastor Craven Engel tirelessly works towards peace.

His mission involves mediating gang conflicts to curtail the violence fueled by the lucrative drug trade. His approach centers on detection, intervention, and attitudinal change.

“Hanover Park’s economy is largely driven by the drug trade,” Pastor Engel explains. “It’s the dominant force.”

He acknowledges apartheid’s enduring impact but stresses the role of generational trauma—manifesting as addiction and family breakdown.

“Drugs fuel unemployment, theft, gang warfare over territory. They are at the heart of the community’s struggles,” says Pastor Engel, estimating that approximately 70% of local children grapple with addiction.

This community of around 50,000 endures almost daily shootings and stabbings, often involving young people as both perpetrators and victims.

“A solely policing approach is insufficient,” Newham emphasizes. “Arresting gang members only replaces them with younger recruits, escalating territorial disputes.”

“How does a child sustain seven head wounds or three back wounds? How is a child hit by a stray bullet?” Pastor Engel questions.

He maintains constant contact with community leaders and gang leaders, mediating conflicts. During a visit, he attempts to broker a ceasefire, even reaching a jailed gang leader.

“If I want something done, it gets done,” the gang boss asserts over the phone. “But I’ll retaliate if attacked.”

Even threats from prison cannot deter Pastor Engel’s relentless pursuit of peace. He remains highly visible in the community.

“The alarming increase in child gang involvement is particularly concerning—recruitment occurs between eight and fifteen years old,” he notes.

While government funding for his program has ceased, he continues his efforts, meeting with both victims and perpetrators. He utilizes reformed gang members to negotiate ceasefires.

Glenn Hans, a former gang member, engages rival gangs, advocating for peace. However, one gang member’s response is chilling: “The more we kill, the more territory we gain; peace isn’t an option for us.”

A ceasefire, eventually reached, crumbles within days following a drive-by shooting.

Yet, some are seeking a way out.

Fernando “Nando” Johnston, a member of the Mongrels gang, seeks help from Pastor Engel.

Pastor Engel describes Johnston as a young man “born into the gang,” with his entire family involved.

“In this life, you’re either jailed or dead,” Johnston states.

“I want to change. I approached the pastor to find a way out.”

He enters a six-to twelve-week rehabilitation program, funded by donations, aiming to address addiction and secure employment.

“You can rebuild your life,” Pastor Engel assures him. “Get a job, earn your own money, and escape this cycle.”

“I’m ready,” Johnston declares, prepared to leave his troubled community.

Loved ones gather to wish him well. His mother, Angeline April, fights back tears, yearning for her son’s survival. “Make the most of this opportunity, Nando,” she pleads.

“I always do, Mum.”

But it’s never been easy.

“Fernando’s father was a gangster, but the father of my other children was a good man,” his mother explains. “Despite my warnings, the children became involved. Raising four boys alone was challenging. I constantly urge him to change, because I love him deeply.”

Two weeks into the program, Johnston is progressing well.

“Nando is stabilizing. He’s in a work program, seeing his family, and recently had a clean drug test,” Pastor Engel reports.

Hope remains scarce, yet it occasionally emerges from the cracks in these war-torn streets.

But not everywhere. Devon and Undean’s home remains amidst a battlefield, a stark reminder of the overwhelming cycle of violence plaguing Cape Town’s edges.

Those caught in the crossfire are often forced into impossible choices.

“Community members, even if opposed to gangs, may not trust the police,” Newham explains. “They doubt police response and fear corruption. The scale of the challenge is immense.”

This sentiment is echoed by the peacemakers on the frontlines. “No one will magically save us—not foreign aid, not our government,” Pastor Engel states. “We must build resilience, foster hope, and grow. Politics has clearly failed us.”

Go to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica

Albert Ojwang died in police custody after being detained for allegedly defaming the deputy police chief.

Many others were injured when a barrier collapsed as MC Alger fans celebrated winning the league, reports say.

Some are beguiled by the Zimbabwean tycoon’s generosity, others alarmed about the source of his wealth.

What should have been a time for Zambia to come together has exposed old enmities.

A selection of the week’s best photos from across the African continent and beyond.