The remains of a British man who perished in a tragic 1959 accident in Antarctica have been discovered within a melting glacier.

A Polish Antarctic expedition located the remains in January, along with artifacts including a wristwatch, radio, and pipe.

The individual has been formally identified as Dennis “Tink” Bell, who, at the age of 25, fell into a crevasse while working for what is now the British Antarctic Survey.

“I had long given up on finding my brother. It is just remarkable, astonishing. I can’t get over it,” David Bell, 86, told BBC News.

“Dennis was one of the many brave personnel who contributed to the early science and exploration of Antarctica under extraordinarily harsh conditions,” stated Professor Dame Jane Francis, director of the British Antarctic Survey.

“Even though he was lost in 1959, his memory lived on among colleagues and in the legacy of polar research,” she added.

It was David who answered the door at his family home in Harrow, London, in July 1959.

“The telegram boy said, ‘I’m sorry to tell you, but this is bad news’,” he recounted. He then informed his parents.

“It was a horrendous moment,” he added.

Speaking from his home in Australia alongside his wife Yvonne, David shared memories of his childhood in 1940s England.

These are the recollections of a younger brother who admired his charming and adventurous older sibling.

“Dennis was fantastic company. He was very amusing. The life and soul of wherever he happened to be,” David said.

“I still can’t get over this, but one evening when me, my mother and father came home from the cinema,” he recalled.

“And I have to say this in fairness to Dennis, he had put a newspaper down on the kitchen table, but on top of it, he’d taken a motorbike engine apart and it was all over the table,” he said.

“I can remember his style of dress, he always used to wear duffel coats. He was just an average sort of fellow who enjoyed life,” he added.

Dennis Bell, nicknamed “Tink,” was born in 1934. He served with the RAF and trained as a meteorologist before joining the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey to work in Antarctica.

“He was obsessed with Scott’s diaries,” David noted, referring to Captain Robert Scott, a pioneer of South Pole exploration who died on an expedition in 1912.

Dennis journeyed to Antarctica in 1958, stationed at Admiralty Bay, a small UK base with roughly 12 personnel on King George Island, located approximately 120 kilometers (75 miles) off the northern coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

The British Antarctic Survey maintains meticulous records, and archivist Ieuan Hopkins has unearthed detailed base camp reports about Dennis’s work and activities on the harsh and “ridiculously isolated” island.

Reading aloud, Mr. Hopkins stated: “He’s cheerful and industrious, with a mischievous sense of humour and fondness for practical jokes.”

Dennis’s responsibilities included launching meteorological weather balloons and transmitting reports to the UK every three hours, which involved starting a generator in sub-zero temperatures.

He was also known as the best cook in the hut and managed the food store during the winter months when resupply was impossible.

Antarctica felt even more remote than it does today, with limited contact with home. David recalled recording a Christmas message at BBC studios with his parents and sister Valerie to be sent to his brother.

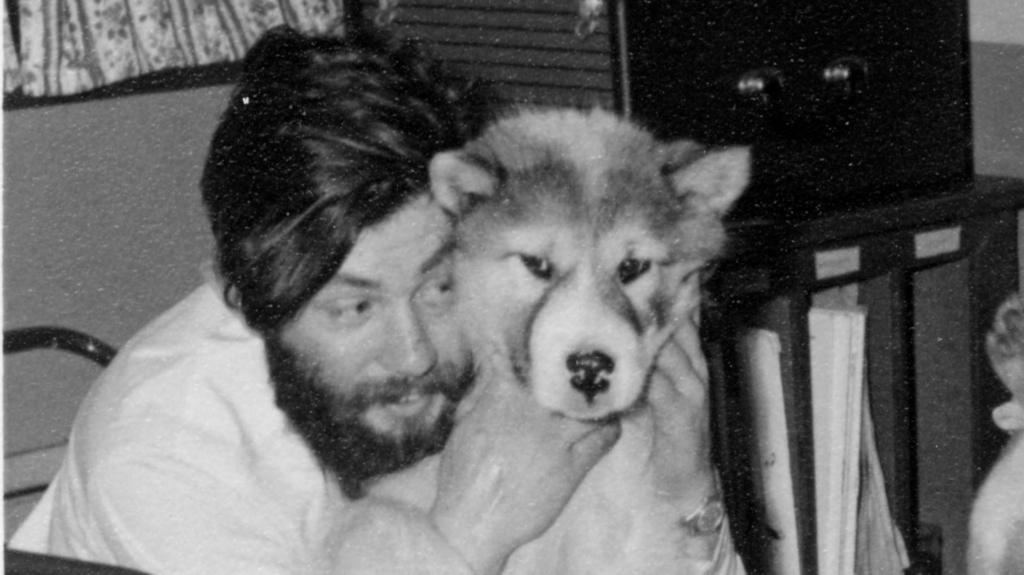

He was particularly known for his affection for the husky dogs used to pull sledges around the island, and he raised two litters of dogs.

He also contributed to surveying King George Island, playing a role in creating some of the first maps of the largely unexplored region.

The accident occurred during a surveying expedition, a few weeks after his 25th birthday.

On July 26, 1959, during the Antarctic winter, Dennis and a colleague named Jeff Stokes departed the base to climb and survey a glacier.

British Antarctic Survey records detail the events that followed and the subsequent rescue efforts.

The snow was deep, and the dogs began to show signs of fatigue. Dennis proceeded ahead alone to encourage them, but he wasn’t wearing his skis. Suddenly, he disappeared into a crevasse, leaving a hole in the snow.

According to the records, Jeff Stokes called into the crevasse, and Dennis responded. He grabbed a rope that was lowered down. The dogs pulled on the rope, and Dennis was hoisted to the edge of the crevasse.

However, he had attached the rope to his belt, possibly due to the angle at which he was positioned. As he reached the edge, the belt broke, and he fell again. His friend called out again, but this time, Dennis did not reply.

“That’s a story I shall never get over,” David said.

The base camp reports regarding the accident are matter-of-fact.

“We heard from Jeff […] that yesterday Tink fell down a crevasse and was killed. We hope to return tomorrow, sea ice permitting,” the report stated.

Mr. Hopkins explained that another man, Alan Sharman, had died weeks earlier, and morale was low.

“The sledge has got back. We heard the sad details. Jeff has badly bitten frostbitten hands. We are not taking any more risks to recover,” the report read the day after the accident.

Reviewing the reports, Mr. Hopkins discovered that earlier in the season, Dennis had constructed the coffin for Alan Sharman.

“My mother never really got over it. She couldn’t handle photographs of him and couldn’t talk about him,” David recounted.

He recalled that two men from Dennis’s base visited the family, bringing a sheepskin as a gesture of sympathy.

“But there was no conclusion. There was no service; there was no anything. Just Dennis gone,” David said.

Approximately 15 years ago, David was contacted by Rod Rhys Jones, chair of the British Antarctic Monument Trust.

According to the trust, 29 individuals have died while working on British Antarctic Territory scientific missions since 1944.

Rod was organizing a voyage for relatives of some of the 29 to experience the remote and spectacular location where their loved ones had lived and died.

David joined the expedition, known as South 2015.

“The captain stopped at the locations and give four or five hoots of the siren,” he said.

The sea ice was too thick for David to reach his brother’s hut on King George Island.

“But it was very, very moving. It lifted the pressure, a weight off my head, as it were,” he said.

It provided him with a sense of closure.

“And I thought that would be it,” he said.

However, on January 29th of this year, a team of Polish researchers working from the Henryk Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station stumbled upon something near their station.

Dennis had been found.

Some bones were discovered in the loose ice and rocks at the base of Ecology Glacier on King George Island. Others were found on the glacier’s surface.

The scientists noted that fresh snowfall was imminent and placed a GPS marker to ensure their “fellow polar colleague” would not be lost again.

A team of scientists, including Piotr Kittel, Paulina Borówka, and Artur Ginter at the University of Lodz, Dariusz Puczko at the Polish Academy of Sciences, and fellow researcher Artur Adamek, carefully recovered the remains over four expeditions.

The area is dangerous and unstable, “criss-crossed with crevasses” and with slopes up to 45 degrees, according to the Polish team.

Climate change is causing significant changes to many Antarctic glaciers, including Ecology Glacier, which is experiencing rapid melting.

“The place where Dennis was found is not the same as the place where he went missing,” the team explained.

“Glaciers, under the influence of gravity, move their mass of ice, and with it, Dennis made his journey,” they added.

Fragments of bamboo ski poles, remnants of an oil lamp, glass cosmetic containers, and pieces of military tents were also collected.

“Every effort was made to ensure that Dennis could return home,” the team stated.

“It’s an opportunity to reassess the contribution these men made, and an opportunity to promote science and what we’ve done in the Antarctic over many decades,” added Rod Rhys Jones.

David remains overwhelmed by the news, reiterating his gratitude to the Polish scientists.

“I’m just sad my parents never got to see this day,” he said.

David will soon visit England, where he and his sister, Valerie, plan to finally lay Dennis to rest.

“It’s wonderful; I’m going to meet my brother. You might say we shouldn’t be thrilled, but we are. He’s been found – he’s come home now.”

The possible planet is just four-and-a-half light years away and may have moons that sustain life.

A former Oceangate employee says he told US authorities about safety concerns with the sub before it imploded.

The reactor would provide power for humans on the Moon but there are questions about feasibility.

The woman, aged about 50, was buried in a Siberian ice cave and discovered millennia later.

Prof Michele Dougherty is the first woman to be appointed to the influential post.