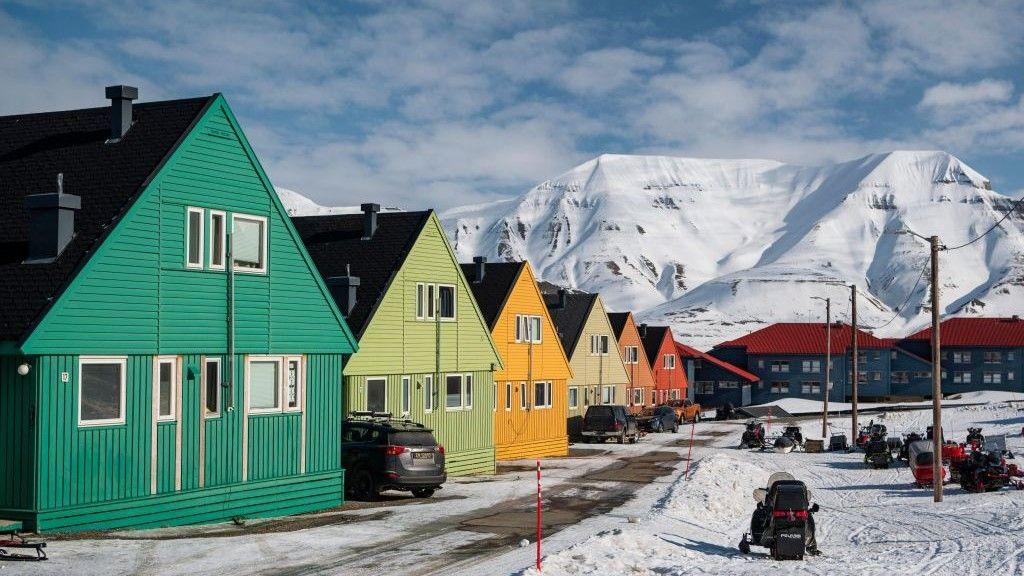

High above the Arctic Circle, the Svalbard archipelago is situated midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole.

This frigid, mountainous, and remote region is home to a substantial polar bear population and a few small settlements.

Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost town, is one such settlement. Just outside, within a decommissioned coal mine, lies the Arctic World Archive (AWA) – a secure underground data vault.

Clients pay to have their data preserved on film within this vault, ensuring its potential survival for centuries.

“Our mission is to ensure information survives technological obsolescence and the passage of time,” explains founder Rune Bjerkestrand, guiding a tour.

With headlamps illuminating the way, we descended a dark passageway, following old railway tracks 300 meters into the mountainside, to reach the archive’s metal door.

Inside the vault, a shipping container is filled with silver packets, each containing reels of film storing the archived data.

“It’s a vast collection of memories and heritage,” Mr. Bjerkestrand notes.

“It encompasses everything from digitized art and literature to music, motion pictures, and more.”

Since its inception eight years ago, the archive has received over 100 deposits from institutions, companies, and individuals across 30+ countries.

These digitized artifacts include 3D scans of the Taj Mahal; sections of ancient Vatican Library manuscripts; satellite Earth observations; and Norway’s iconic “The Scream” by Edvard Munch.

The AWA is a commercial venture, utilizing technology provided by Piql, a Norwegian data preservation company also led by Mr. Bjerkestrand.

Inspired by the nearby Global Seed Vault, it serves as a repository for data recovery following natural or human-caused disasters.

“Today, information and data face numerous threats,” Mr. Bjerkestrand states. “Terrorism, war, and cyberattacks pose significant risks.”

He considers Svalbard the ideal location for a secure data storage facility.

“It’s far removed from conflicts, crises, and disasters. What could be safer?”

The underground vault’s dark, dry, and consistently sub-zero temperatures create ideal conditions for long-term film preservation, according to Mr. Bjerkestrand.

Even potential permafrost thaw due to global warming shouldn’t compromise the vault’s robustness, he assures.

A separate large metal box at the chamber’s rear houses GitHub’s Code Vault.

This contains hundreds of reels of open-source code – the foundational elements of computer operating systems, software, websites, and apps.

Programming languages, AI tools, and all active public repositories from its 150 million users are also archived here.

“Securing software’s future is crucial for humanity; it’s integral to our daily lives,” emphasizes GitHub’s chief operating officer, Kyle Daigle.

His company explored various long-term storage solutions, acknowledging the challenges. “Some methods offer long-term storage, but require specific technology for retrieval.”

At Piql’s southern Norway headquarters, data files are encoded onto photosensitive film.

“Data is a sequence of bits and bytes,” explains senior product developer Alexey Mantsev, demonstrating film passing through a spool.

“We convert this sequence into images. Each image contains approximately eight million pixels.”

The processed film appears grey, but closer inspection reveals a pattern resembling numerous tiny QR codes.

This information is immutable and easily retrievable, Mr. Mantsev clarifies. “We can scan and decode it like a hard drive, but from film.”

A key concern with long-term storage is future comprehension and retrieval. Piql addresses this by incorporating a magnified, optically readable guide onto the film itself.

With daily data usage and generation exceeding previous levels, experts warn of a potential digital Dark Age as technology renders older software and hardware obsolete.

Current file formats may face the same fate as floppy disks and DVDs.

Numerous firms offer long-term data storage solutions.

LTO (Linear Tape Open) magnetic tape cassettes are common, but newer innovations promise to revolutionize information preservation.

For instance, Microsoft’s Project Silica uses 2mm-thick glass panes for data storage via lasers. Scientists at the University of Southampton created a 5D memory crystal, archiving the human genome.

This is also stored in the Memory of Mankind repository, an Austrian salt mine vault safeguarding historical documents.

The Arctic World Archive accepts deposits thrice yearly. During our visit, recordings of endangered languages and Chopin’s manuscripts were among the latest additions.

Photographer Christian Clauwers, documenting South Pacific islands threatened by sea-level rise, also contributed his work.

“I deposited footage and photographs, visual records of the Marshall Islands,” he explains.

“The islands’ highest point is three meters, and they face severe climate change impacts.”

“The experience was humbling and surreal,” shares archivist Joanne Shortland, after depositing Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust records, engineering drawings, and photographs of historic car models.

“Many of our formats are becoming obsolete. Maintaining accessibility over 20 or 30 years requires constant file format updates. The digital world presents numerous challenges.”

The US currently has no high-speed rail services, but two are under construction, and more planned.

The planned layoffs mean the Japanese carmaker has now cut about 15% of its workforce in the past year.

Chinese online retailers had previously relied on the “de minimis” loophole to ship low-value items to the US.

Giant tyre firms are testing tyres that can survive conditions on the Moon and Mars.

The government say the findings, shown on an open source map, present a worrying picture.