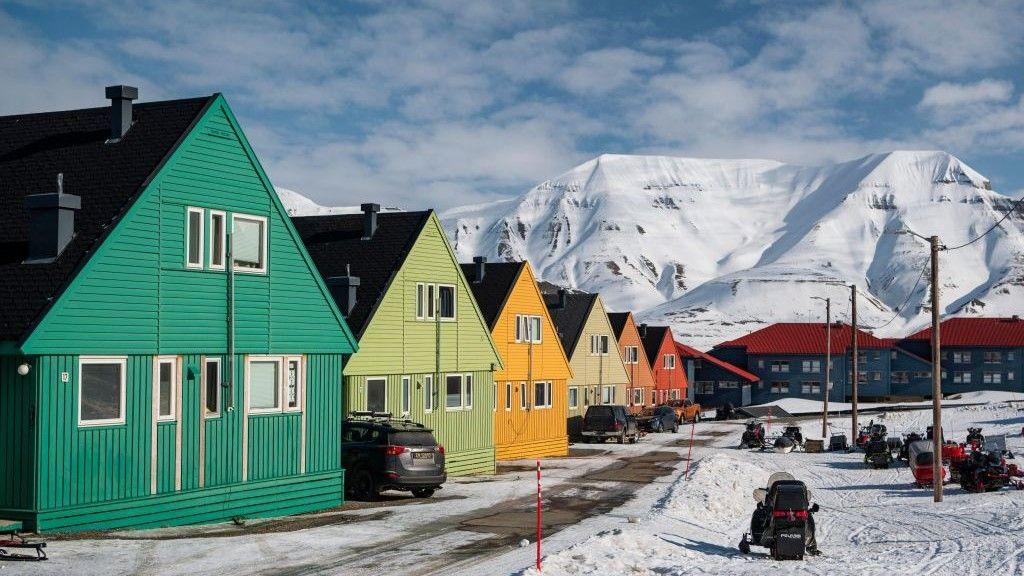

High above the Arctic Circle, the Svalbard archipelago lies midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole.

This remote, mountainous, and frozen land is home to numerous polar bears and a few small settlements.

Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost town, is one such settlement. Just outside, within a decommissioned coal mine, resides the Arctic World Archive (AWA)—an underground data vault.

Clients pay to have their data stored on film within this vault, potentially for centuries.

“Our mission is to ensure information survives technological obsolescence and the passage of time,” explains founder Rune Bjerkestrand, guiding us inside.

With headlamps illuminating our path, we followed old rail tracks 300 meters into the mountain, reaching the archive’s metal door.

Inside the vault, a shipping container holds silver packets brimming with film reels containing the archived data.

“It’s a vast collection of memories and heritage,” Mr. Bjerkestrand notes.

“It encompasses everything from digitized artwork and literature to music and motion pictures—you name it.”

Since its inception eight years ago, the archive has received over 100 deposits from institutions, companies, and individuals across 30+ countries.

Among the digitized artifacts are 3D scans of the Taj Mahal; sections of ancient Vatican Library manuscripts; satellite Earth observations; and Edvard Munch’s iconic painting, “The Scream.”

The AWA operates commercially, utilizing technology provided by Piql, a Norwegian data preservation company also led by Mr. Bjerkestrand.

Its inspiration stems from the Global Seed Vault, located nearby—a repository for crop seeds to safeguard against disasters.

“Today, information and data face numerous threats,” Mr. Bjerkestrand states. “Terrorism, war, cyberattacks—the list goes on.”

He considers Svalbard ideally suited for a secure data storage facility.

“It’s incredibly remote! Far from wars, crises, terrorism, and disasters. What could be safer?”

The underground vault maintains sub-zero temperatures year-round—ideal conditions, according to Mr. Bjerkestrand, for preserving the film for centuries. Even potential permafrost thaw due to global warming shouldn’t compromise the vault’s integrity, he assures.

Another large metal box at the chamber’s rear houses GitHub’s Code Vault.

The software developer has archived hundreds of reels of open-source code—the foundation of computer operating systems, software, websites, and apps.

Programming languages, AI tools, and every active public repository on their platform, contributed by 150 million users, are stored here.

“Securing software’s future is crucial for humanity; it’s integral to our daily lives,” says GitHub’s COO, Kyle Daigle.

His firm explored numerous long-term storage solutions, acknowledging the inherent challenges. “Some existing mechanisms offer longevity, but require specific technology for retrieval.”

At Piql’s southern Norway headquarters, data files are encoded onto photosensitive film.

“Data is a sequence of bits and bytes,” explains senior product developer Alexey Mantsev, demonstrating the film’s passage through a spool.

“We convert the bit sequence from client data into images. Each image [or frame] boasts about eight million pixels.”

The developed film appears grey, but closer inspection reveals a dense array of tiny QR codes.

The information is immutable and easily retrievable, Mr. Mantsev explains. “We scan and decode the data like reading from a hard drive, except the source is film.”

A key concern with long-term storage is future comprehension and retrieval. Piql addresses this by including a magnified, optically readable guide on the film.

Data usage and generation are at an all-time high, yet experts warn of a potential digital Dark Age as technological advancements render older software and hardware obsolete.

Current file formats might face a similar fate as floppy disks and DVDs.

Various firms offer long-term data storage.

LTO (Linear Tape Open) magnetic tapes are prevalent, but newer innovations promise to revolutionize information preservation.

For instance, Microsoft’s Project Silica uses 2mm-thick glass panes for data storage via lasers.

Meanwhile, the University of Southampton created a 5D memory crystal storing the human genome, also housed in the Memory of Mankind repository—an Austrian salt mine vault.

The Arctic World Archive receives deposits thrice yearly. During our visit, recordings of endangered languages and Chopin’s manuscripts were among the latest additions.

Photographer Christian Clauwers, documenting South Pacific Islands threatened by sea-level rise, also contributed his work.

“I deposited footage and photography—visual records of the Marshall Islands,” he explains.

“The islands’ highest point is three meters; they face immense climate change impacts.”

“It was humbling and surreal,” shares archivist Joanne Shortland of the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust after depositing records, engineering drawings, and photos of classic car models.

“I have many obsolete formats. Maintaining accessibility for 20 or 30 years requires constant file format updates. The digital world presents numerous challenges.”

The planned layoffs mean the Japanese carmaker has now cut about 15% of its workforce in the past year.

Chinese online retailers had previously relied on the “de minimis” loophole to ship low-value items to the US.

Giant tyre firms are testing tyres that can survive conditions on the Moon and Mars.

The government say the findings, shown on an open source map, present a worrying picture.

As the president goes to Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE he wants them to buy more from the States.