This video can not be played

Robin Smith’s record-breaking 167

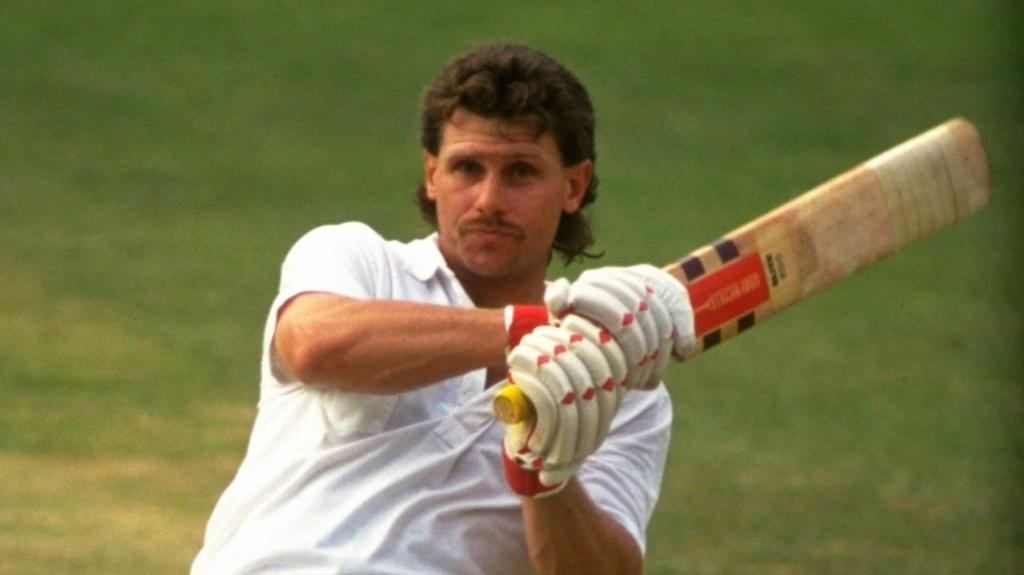

Robin Smith, who has died at the age of 62, was renowned as one of the finest players of fast bowling during an era when the England team often faced considerable challenges.

For nearly a decade, Smith, with his distinctive moustache, was a familiar and courageous figure for England supporters, often seen confronting the formidable West Indies pace attack or battling against the relentless Australians.

His signature shot, an immensely powerful square cut, established him as a feared opponent and earned him admiration across the globe.

Remembered for his loyalty to friends and respect from opponents, Smith faced significant personal battles after retirement, with his struggles involving mental health and alcoholism becoming public in later years.

Former England batter Robin Smith dies aged 62

Smith faced some difficult tussles against Shane Warne in the Test arena, but the Australia legend eventually became a firm friend and a Hampshire team-mate

Robin Arnold Smith was born in Durban, South Africa in 1963 to British-born parents, and made his name as a schoolboy prodigy in cricket and rugby.

He served as the model for images in a coaching book authored by the esteemed South African Test opener Barry Richards, who became a lifelong friend.

His parents went so far as to purchase the house next door, demolish it, and construct a cricket pitch complete with an early bowling machine for Robin and his elder brother Chris to practice on. They also hired ex-Natal player Grayson Heath as their coach.

The younger Smith reached the Natal squad at the age of 17, fulfilling duties such as carrying drinks for figures like Richards and another South African great, Mike Procter. However, an early opportunity arose through his brother.

Chris Smith had played for Glamorgan 2nd XI in 1979, scoring a century against Hampshire, who were sufficiently impressed to offer him a contract for 1980 as a replacement overseas player while Gordon Greenidge was with West Indies.

When Chris returned in 1981, 17-year-old Robin accompanied him and was rapidly signed after a successful trial.

With a Walsall-born father and Edinburgh-born mother, the Smith brothers had a pathway into English cricket at a time when South Africa’s apartheid regime resulted in a continued international ban.

However, regulations stipulated that despite their parentage, they were required to serve a four-year qualification period. Consequently, Chris was considered an ‘overseas’ player until 1983, and Robin until 1985.

Smith was initially nicknamed ‘Judge’ in his teens in South Africa because his long, wavy hair resembled a judge’s wig

Robin had to patiently await opportunities to play as an overseas player when Greenidge or Malcolm Marshall were unavailable.

His Hampshire debut was against Pakistan at Bournemouth in 1982. Perhaps foreshadowing future challenges against spin, the teenager was bowled round his legs by the shrewd leg-spinner Abdul Qadir.

In contrast, 2nd XI bowlers faced a barrage, with coach Peter Sainsbury lamenting the cost of replacing balls that Smith had dispatched out of the ground.

With Greenidge and Marshall absent for the 1983 World Cup and then with West Indies in 1984, Smith had an extended period in the side and made an immediate impact upon becoming England-qualified in 1985, amassing over 1,500 runs that summer.

While Chris earned eight Test caps, observers recognized that Robin was likely to outshine his brother. Robin’s England call-up arrived in 1988, soon after a destructive innings in the Benson & Hedges Cup final at Lord’s.

The news broke on the morning of a Sunday League game at Edgbaston.

While the Smith parents steadfastly followed their sons around the country with Hampshire, father John was away that weekend, watching Seve Ballesteros win The Open at Royal Lytham. Mother Joy was overcome with emotion upon hearing of Robin’s international selection.

Even when not dressed as Mickey and Minnie Mouse, Smith and Allan Lamb shared a strong bond on and off the field. Smith proudly wrote in 2019 that their Test partnership average of 79 was the highest by an England pair since the Second World War

Smith entered Test cricket with England in disarray against West Indies. His first Test at Headingley was under Chris Cowdrey, one of four captains England used in the summer of 1988.

But Smith gave early notice that he was not overawed by a four-man pace attack headed by his great friend Marshall, hitting 38 on debut and sharing a century stand with fellow South Africa-born batter Allan Lamb.

This was an era when England chopped and changed players frequently, using 29 in the 1989 Ashes, but Smith soon established himself as one of the important cogs around which the team was built.

His maiden Test century was a superlative 143 against Australia in Manchester, and Smith’s bravery against fast bowling became a trademark of his game.

Wearing a blue England helmet without a visor or grille, he was at his happiest pulling, hooking or cutting the quicks.

Whether facing Caribbean bouncers or verbals from his old adversary Merv Hughes, he gave as good as he got.

This video can not be played

‘He was a cool cricketer’ – Chief cricket reporter Stephan Shemilt pays tribute to Robin Smith

While Smith’s figures in one-day internationals did not match his Test statistics, his unbeaten 167 against Australia at Edgbaston in 1993 remained an England ODI record until 2016.

Smith was single-minded about batting – his first book was entitled Quest for Number One. Indeed, the International Cricket Council’s retrospective world rankings had him at number two in 1991,, external a year Smith described as his “perfect summer”, behind his captain Graham Gooch.

Despite being offered a trial with baseball’s New York Mets – which could have potentially dwarfed his cricket earnings in an era before lucrative central contracts – he remained loyal to England, while still giving his all for Hampshire between Tests, winning man-of-the-match awards in two Lord’s finals.

But this was an England side in transition. Coach Micky Stewart, who Smith adored and would describe as “my second father”, departed at the end of the 1992 summer, which was also a last hurrah for Lamb, David Gower and Ian Botham.

“It meant my dressing-room support network disappeared at a stroke,” Smith later wrote. “Though I didn’t know it at the time, I would never quite be the same player again.”

Smith’s Test average of 43.67 compares favourably with many of his England team-mates such as Graham Gooch (42.58), Alec Stewart (39.54), Michael Atherton (37.69), Nasser Hussain (37.18), Allan Lamb (36.09), Mike Gatting (35.55) and Graeme Hick (31.32). Only David Gower (44.25) and the late Graham Thorpe (44.66) averaged higher

Having learned to bat on hard, bouncy tracks in South Africa, a quirk of the calendar meant Smith was 36 Tests and more than four years into his England career before he played a Test on the subcontinent.

It became a perception that Smith struggled against high-class spin bowling, and in 1993, after averaging only 24 in India before being dismissed seven times in 10 innings by either Shane Warne or Tim May in the Ashes, that perception became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Smith had an operation after that summer on the nagging shoulder injury which destroyed his bullet-like throw from the boundary, but did not flourish under the man-management of Stewart’s replacement Keith Fletcher or new chairman of selectors Ray Illingworth.

Having been an automatic pick for years, Smith was suddenly under the spotlight, his confidence dented by Fletcher’s public criticism of his off-field activities, which included a company making cricket equipment.

South Africa by now had been readmitted to international cricket, and Smith was hugely disappointed to be dropped for the first home series against the country of his birth – and then omitted for the 1994-95 Ashes.

Injuries earned Smith a recall against West Indies in 1995 – which included a fractured cheekbone courtesy of Ian Bishop – and a tour ticket to South Africa that winter, but he continued to feel publicly undermined by Illingworth, who was now doubling up as coach after Fletcher’s sacking.

After they crashed out of a chaotic 1996 World Cup on the subcontinent, Smith’s England career was over at the age of 32.

‘Hard when your time has come’ – Smith

Archive: Robin Smith opens up to BBC Sport about his post-cricket struggles

This video can not be played

Robin Smith: Former Hampshire and England batter reflects on life after cricket

Smith continued to play for Hampshire, captaining them – with a little reluctance – between 1998 and 2002, while dreaming of an England recall that never came.

He felt heartbroken when he was told he would not be offered another Hampshire contract at the end of 2003, and would later open up in his 2019 book about the demons he faced in retirement, explaining how his cricketing self and private self diverged.

“The Judge was a fearless warrior; Robin Arnold Smith was a frantic worrier,” he wrote.

Relocating to Perth, Western Australia, to join his brother and parents who had moved there, he battled with mental health issues, the break-up of his marriage, and alcohol problems.

But the warm reaction from the cricket world to his book, and the life struggles he confessed, reinforced how fondly Robin Smith will always be remembered.

He wrote: “I wasn’t one of the all-time greats, but if people remember me as a good player of raw pace bowling then I’m chuffed with that because it’s something I worked so hard on.”

If you need information or support around topics raised in this article go to the BBC Action Line page.