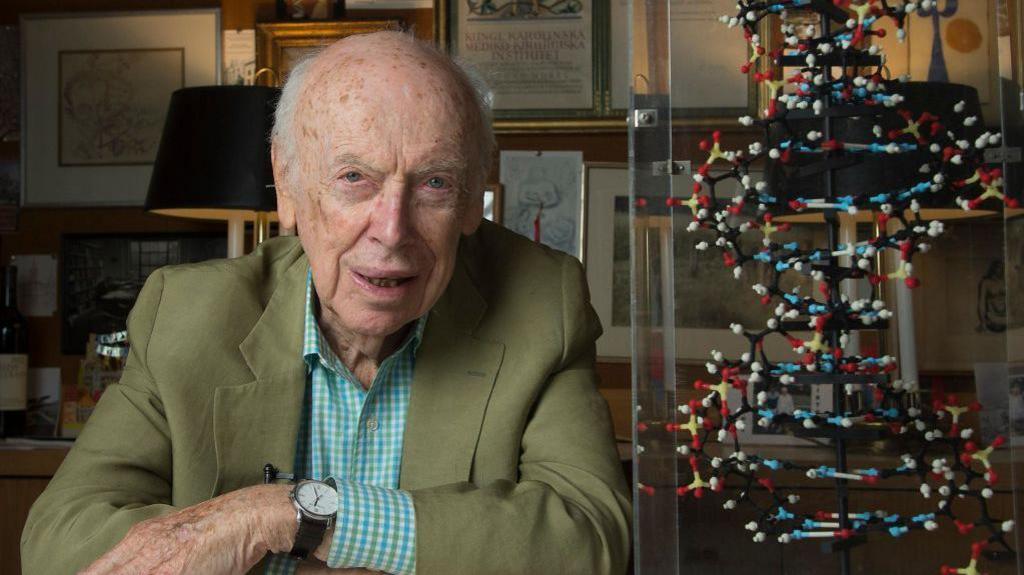

In February 1953, two scientists entered a Cambridge pub with a bold declaration: they had discovered “the secret of life.” It was not an exaggeration.

One was James Watson, an American biologist working at the Cavendish Laboratory; the other was his British research partner, Francis Crick.

Their discovery – the structure and function of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA – is considered as important to modern science as the work of Mendel and Darwin.

The full impact of their achievement would gradually unfold through decades of subsequent research by geneticists.

It also opened complex scientific and ethical questions – including human cloning, designer babies, and genetically modified foods.

By demonstrating that DNA has a three-dimensional, double-helix shape, Watson and Crick unlocked how cells function and how traits are passed through generations.

“When we saw the answer, we had to pinch ourselves,” Watson said. “We realised it probably was true because it was so pretty.”

The discovery earned them the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1962 and secured their place among history’s most influential scientific thinkers.

It also meant that any controversial remarks they made would be headline news.

And Watson had a history of controversial statements, most notably speculating about a link between race and intelligence.

When he initially suggested that Black people are less intelligent, London’s Science Museum cancelled a planned lecture, stating that Watson’s views went “beyond the point of acceptable debate.”

He also suggested, “when you interview fat people, you feel bad, because you know you’re not going to hire them,” and questioned whether beauty could – and should – be genetically encouraged.

Watson was heavily criticized for suggesting that women should have the right to abort a fetus if tests indicated it would be homosexual.

He maintained he was simply advocating for choice, that it would be equally acceptable to prefer homosexual offspring, and that the desire for grandchildren was natural.

He alienated many colleagues, labeling fellow academics “dinosaurs,” “deadbeats,” “fossils,” and “has-beens” in his autobiography, “Avoid Boring People.”

In 2014, he became the first living Nobel laureate to auction his medal, partly to fund future scientific discovery. A Russian tycoon purchased it for $4.8 million (£3 million) and promptly returned it to him.

James Dewey Watson was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, to a family that valued “books, birds, and the Democratic Party.”

He was the only son of Jean and James, descendants of English, Scottish, and Irish settlers.

His political inclination came from his mother, who worked for the Democrats. Their basement was used as a polling station during elections.

His father’s interests were science and bird-watching. Young Watson accompanied him on birding trips, learning that science requires careful observation of nature.

This left little room for faith. Raised Catholic by his mother, Watson described himself as having “escaped from that religion.”

“The luckiest thing that ever happened to me was that my father did not believe in God,” he said.

The Great Depression of the 1930s led to his father’s salary being cut in half, prompting a quick trip to the bank to withdraw their remaining savings.

Watson shared a tiny attic room with his younger sister, Betty.

He was a skinny teenager told to drink milkshakes to “fatten him up.” Socially awkward, he was once expelled from school due to poor grades, his performance impacted by scarlet fever.

“None of my classmates thought I would amount to much,” he recalled.

He did not consider himself precocious, yet he received a scholarship to the University of Chicago at 15.

He attributed it to “my mother knowing the dean of admissions.”

University freed him from the complex social hierarchies of school life where popularity and physical stature mattered most, providing an environment for a brilliant but awkward teenager to excel.

Watson initially considered majoring in ornithology, but switched to genetics after reading Erwin Schrödinger’s “What is Life?”

He described the University of Chicago as an “idyllic academic institution” where he developed “critical thinking skills and an ethical obligation not to tolerate fools who hindered his pursuit of truth.”

The prevailing scientific view was that genes were proteins capable of self-replication. DNA was dismissed as “stupid,” existing only to support protein.

Watson became intrigued by diffraction, a technique using X-rays to reveal the inner structures of atoms.

He became convinced that DNA had its own structure and resolved to find it, believing England was the ideal place.

At Cambridge, he met Francis Crick, a physicist with “extraordinary conversational ability” and “the loudest laugh I have ever known.”

They began building large-scale models of potential DNA structures, testing them against existing evidence. In one of science’s most significant controversies, not all the evidence was theirs.

Watson and Crick were racing against a team at King’s College London, consisting of Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. Watson and Crick had a good relationship with Wilkins, but a poor one with Franklin.

Wilkins corresponded with Watson and Crick, sometimes sharing his thoughts and insights.

Franklin, however, was different. She was an experienced chemist and expert in diffraction.

With her student Raymond Gosling, she photographed the patterns created by X-rays bouncing off DNA molecules.

Watson and Crick found Franklin “hostile” and thought she jealously guarded her research and worked in isolation.

They were dismissive and critical of her appearance, but Watson was willing to look at her work when Wilkins offered, without Franklin’s permission.

The critical evidence was Photo 51.

It showed a fuzzy pattern of X-rays that fascinated Watson and Crick, prompting a flurry of model building, with each theory tested against the new information.

From this, they deduced that DNA must have a three-dimensional, double-helix structure – like a twisted ladder with rungs of alternating salt and phosphate groups.

Their key conclusions were that each separated strand could serve as a template to create the other, and that the order of the “rungs” was a code.

They reasoned that understanding this code could unlock the mysteries of life.

Wilkins congratulated his rivals on winning what had been a heated race.

When he received the 1962 Nobel Prize for Medicine alongside Watson and Crick, Franklin was not there.

She had died of ovarian cancer at just 37.

According to Nobel Prize rules, only living individuals can be honored. Franklin’s supporters felt she had been wronged twice.

Later, Watson and his wife, Elizabeth, moved to Harvard, where he became a biology professor and had two sons – one of whom suffered from schizophrenia.

He then took over the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York State, transforming it into one of the world’s leading scientific research institutes.

In 1968, his account of the race to discover DNA’s structure, “The Double Helix,” was published.

It is a painful examination of the story, recounting the personalities, controversies, and bitterness from his perspective. He considered calling the book “Honest Jim.”

But despite Professor Watson’s academic achievements, his later career was overshadowed by his controversial public statements.

In 1990, the journal “Science” wrote that “to many in the scientific community, Watson has long been something of a wild man, and his colleagues tend to hold their collective breath whenever he veers from the script.”

At a conference in 2000, Watson lived up to that reputation.

He suggested that Black people might have higher sex drives than whites, arguing that melanin, which gives skin its color, boosted libido.

“That’s why you have Latin lovers,” he told the delegates. “You never have an English lover, only an English patient.”

He suggested that humanity might screen out stupid people through genetic testing, then gave an interview that severely damaged his reputation.

While promoting his autobiography, Watson spoke to the Sunday Times.

The article quoted him as being “gloomy about the prospect of Africa” because “our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – whereas all the testing says not really.”

Watson admitted this was a “hot potato” and expressed his hope that everyone was equal.

However, he said, “People who have to deal with black employees find this not true.”

He later apologized, but his research institute stripped him of executive power, making him chancellor emeritus.

James Watson spent the rest of his life raising money for medical research, often using emotional appeals.

“Nothing attracts money like a quest for the cure to a terrible disease,” he said.

He continued to make waves, warning that “Viagra is fighting evolution.”

He also argued that men should store sperm in their teens to avoid the increased risk of fathering children with developmental issues.

He repeated his views on the link between race and intelligence in a 2019 documentary, leading the scientific community to revoke his remaining honorary positions.

He will be remembered as the “Godfather of DNA,” the man who unlocked the secrets of life, and a world-class controversialist who often spoke without thinking.

The Nobel Prize winner felt ostracized by the scientific community over his comments on race and intelligence.

A new 21-hectare site will be added to RSPB Otmoor, in Oxfordshire.

The structure at Queen’s Park in Bournemouth is made from recycled plastic.

The Rescuing Rocks and Overgrown Relics scheme will focus on former mining and quarrying locations.

Campaigners take to the banks of the River Dart, calling for the right to access all English rivers.