A groundbreaking discovery in northwest Kenya suggests that the earliest humans, who lived millions of years ago, may have been innovators.

Researchers have unearthed evidence indicating that hominins inhabiting the Namorotukunan archaeological site approximately 2.75 million years ago consistently utilized stone tools over a period of 300,000 years.

Previous understandings of early human tool use portrayed it as infrequent, characterized by sporadic development and rapid abandonment.

The Namorotukunan findings offer the first compelling evidence that this technology was transmitted across countless generations.

Prof. David Braun of George Washington University, who led the research, stated that the find, published in Nature Communications, strongly suggests a fundamental reassessment of human evolution.

“We had previously hypothesized that tool use might have been a transient phenomenon, quickly emerging and then disappearing. However, the persistence of the same tools over 300,000 years contradicts this notion,” he explained.

“This discovery demonstrates a long-term behavioral pattern, indicating that tool use among humans and their ancestors likely originated much earlier and was more continuous than previously believed.”

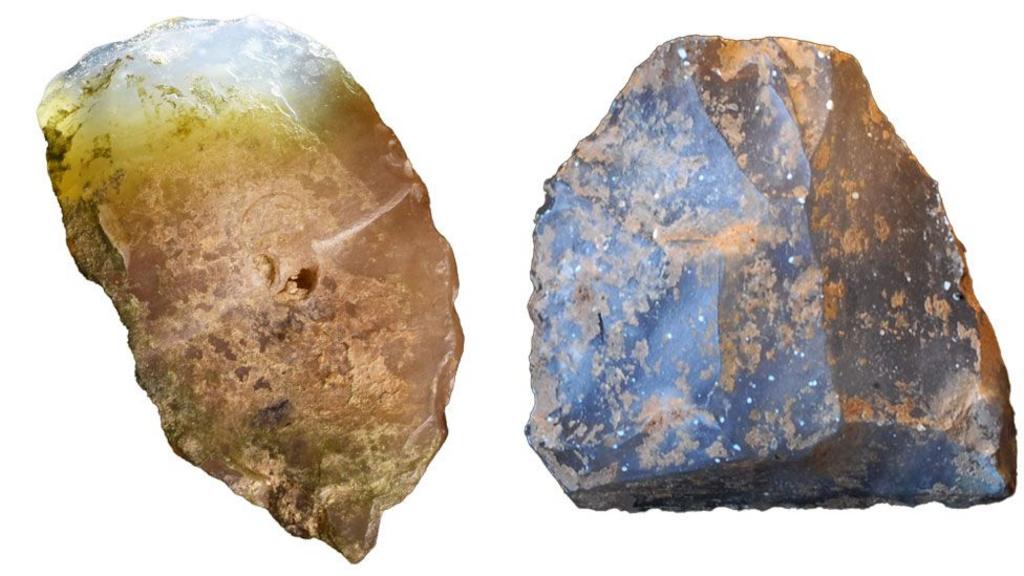

Over a decade, archaeologists at Namorotukunan unearthed 1,300 sharp flakes, hammerstones, and stone cores, all meticulously crafted by striking rocks collected from riverbeds. These tools were created using the Oldowan technology, the earliest known widespread method for crafting stone tools.

The same tool types appear in three distinct layers, with deeper layers representing earlier points in time. Dr. Dan Palcu Rolier of the University of São Paulo in Brazil, the research team’s senior geoscientist, noted that many of the stones were specifically selected for their quality, implying that the toolmakers were skilled and discerning in their choices.

“The level of sophistication evident at this site is remarkable,” Dr. Palcu Rolier told BBC News.

“These individuals possessed a keen understanding of geology, knowing how to locate the best raw materials. The resulting stone tools are exceptional; some are so sharp that we could cut ourselves on them.”

Geological evidence suggests that tool use likely played a crucial role in the survival of these early humans during periods of significant climate change.

Rahab N. Kinyanjui, a senior scientist at the National Museums of Kenya, explained that the landscape underwent a transformation from lush wetlands to arid, fire-prone grasslands and semi-deserts.

While such abrupt environmental shifts typically necessitate adaptation through evolution or migration for animal populations, the toolmakers in this region were able to flourish by leveraging technology rather than relying on biological adaptation, according to Dr. Palcu Rolier.

“Technology empowered these early inhabitants of East Turkana to persist in a rapidly evolving environment by modifying their methods of acquiring food, rather than undergoing physical adaptation.”

The presence of stone tools in multiple layers indicates that these early humans consistently defied biological evolution by developing strategies to control their environment, rather than being controlled by it.

Dr. Palcu Rolier emphasized that this occurred at the dawn of humanity.

“Tool use eliminated the need for bodily modifications to adapt to environmental changes. Instead, they created the technology required to access food, including tools for processing animal carcasses and extracting plants.”

Evidence at the site, such as fractured animal bones bearing cut marks from stone tools, supports this assertion. Throughout these environmental changes, the early humans consistently relied on meat as a source of sustenance.

“Technology provided these early inhabitants with a distinct advantage,” Dr. Palcu Rolier stated.

“They were able to access a diverse range of food sources as the environment shifted. While their primary sources of sustenance changed, technology allowed them to overcome these challenges and exploit new food resources.”

Around 2.75 million years ago, the region was inhabited by some of the earliest humans, who possessed relatively small brains. These early humans coexisted with their evolutionary predecessors, australopithecines, a pre-human group characterized by larger teeth and a combination of chimpanzee and human traits.

The tool users at Namorotukunan were likely either one of these groups or a combination of both.

The discovery challenges the prevailing notion among human evolution experts that sustained tool use emerged much later, between 2.4 and 2.2 million years ago, when humans had developed relatively larger brains, according to Prof. Braun.

“The prevailing argument is that a significant increase in brain size occurred during this period, and tool use enabled the sustenance of this larger brain.”

“However, the findings at Namorotukunan demonstrate that these early tools were utilized before this increase in brain size.”

“We have likely underestimated the capabilities of these early humans and their ancestors. We can now trace the origins of our ability to adapt to change through technology much further back than previously thought, potentially as far back as 2.75 million years ago, and possibly even earlier.”