“`html

China’s paramount leaders are convening in Beijing this week to deliberate on the nation’s pivotal objectives and ambitions for the remainder of the decade.

The Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, the country’s preeminent political body, assembles annually, or nearly so, for a week-long series of meetings known as a Plenum.

The decisions made at this Plenum will ultimately underpin China’s next Five-Year Plan – the strategic roadmap that the world’s second-largest economy will adhere to between 2026 and 2030.

While the comprehensive plan is not expected until next year, officials are anticipated to offer insights into its key components on Wednesday, with further details typically emerging within a week thereafter.

“Western policy operates on election cycles, but Chinese policy-making functions on planning cycles,” observes Neil Thomas, a fellow specializing in Chinese politics at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

“Five-Year Plans articulate China’s desired achievements, signal the leadership’s intended direction, and channel state resources toward these predetermined objectives,” he adds.

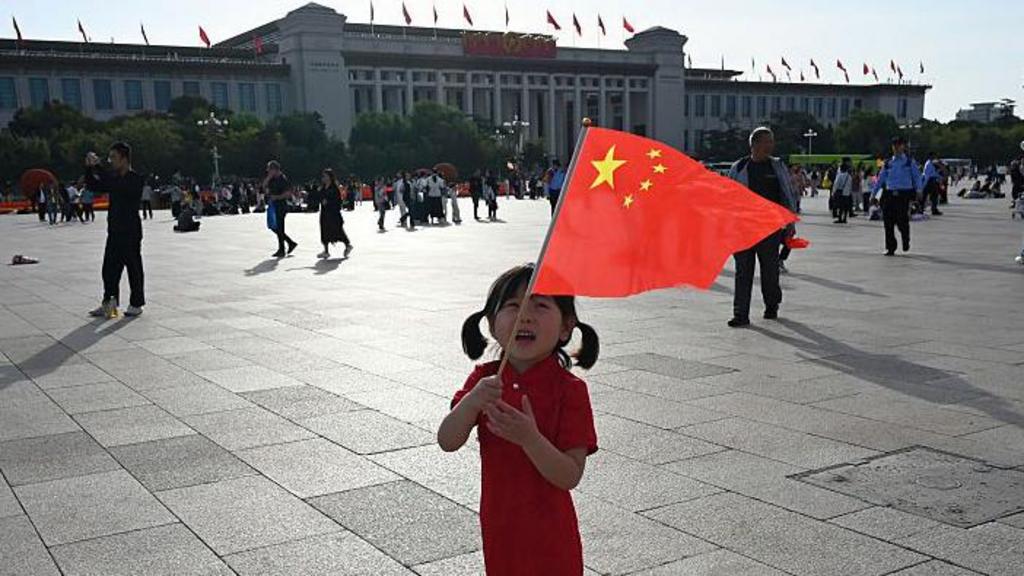

Although the image of hundreds of officials in suits engaging in planning may seem unremarkable, history demonstrates that their decisions often have far-reaching global implications.

Here are three instances where China’s Five-Year Plans reshaped the global economic landscape.

Pinpointing the precise moment China embarked on its path to becoming an economic powerhouse is challenging, but many within the Party attribute it to December 18, 1978.

For nearly three decades, China’s economy had been rigidly controlled by the state. However, Soviet-style central planning had failed to deliver widespread prosperity, leaving many mired in poverty.

The nation was still recovering from Mao Zedong’s devastating rule. The Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution – initiatives spearheaded by Communist China’s founder to reshape the nation’s economy and society – resulted in millions of fatalities.

Speaking at the 11th Committee’s Third Plenum in Beijing, the country’s new leader, Deng Xiaoping, declared that it was time to embrace certain elements of the free market.

His policy of “reform and opening up” became integral to the subsequent Five-Year Plan, which commenced in 1981.

The establishment of free-trading Special Economic Zones – and the foreign investment they attracted – transformed the lives of people in China.

According to Mr. Thomas, the objectives of that Five-Year Plan could not have been achieved more definitively.

“China today surpasses the wildest aspirations of people in the 1970s,” he states. “In terms of restoring national pride and establishing its position among the world’s great powers.”

However, it also fundamentally reshaped the global economy. By the 21st century, millions of Western manufacturing jobs had been outsourced to new factories in China’s coastal regions.

Economists have termed this “the China shock,” and it has been a significant factor in the rise of populist parties in former industrial areas of Europe and the United States.

For example, Donald Trump’s economic policies – his tariffs and trade wars – were designed to repatriate American manufacturing jobs lost to China over the preceding decades.

China’s status as the world’s workshop was solidified upon its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. However, at the turn of the century, the Communist Party leadership was already strategizing its next move.

It was wary of China falling into the so-called “middle-income trap.” This occurs when a developing country can no longer offer ultra-low wages but lacks the innovative capacity to create the high-end goods and services of an advanced economy.

Therefore, instead of merely focusing on inexpensive manufacturing, China needed to identify what it termed “strategic emerging industries” – a term first officially used in 2010. For China’s leaders, this encompassed green technology, such as electric vehicles (EVs) and solar panels.

As climate change gained increasing prominence in Western politics, China mobilized an unprecedented amount of resources into these nascent industries.

Today, China is not only the undisputed global leader in renewables and EVs but also possesses a near-monopoly over the rare earth supply chains essential for their production.

China’s dominance over these critical resources – which are also crucial for chip-making and artificial intelligence (AI) – now places it in a position of considerable global influence.

Consequently, Beijing’s recent decision to tighten export controls on rare earths was characterized by Trump as an attempt to “hold the world captive.”

Although “strategic emerging forces” was formally enshrined in the subsequent Five-Year Plan in 2011, green technology had been identified as a potential engine of growth and geopolitical power by China’s then-leader Hu Jintao in the early 2000s.

“This aspiration for China to achieve greater self-reliance in its economy, technology, and freedom of action has a long history – it is ingrained in the very fabric of Chinese Communist Party ideology,” explains Neil Thomas.

This may explain why China’s more recent Five-Year Plans have shifted their focus to “high-quality development,” formally introduced by Xi Jinping in 2017.

This entails challenging American dominance in technology and positioning China at the forefront of the sector.

Domestic successes such as the video-sharing app TikTok, telecommunications giant Huawei, and even DeepSeek, the AI model, are all testaments to China’s technological boom this century.

However, Western countries increasingly perceive this as a threat to their national security. The ensuing bans or attempted bans on popular Chinese technology have affected millions of internet users worldwide and have ignited contentious diplomatic disputes.

Until now, China has fueled its technological successes using American innovation, such as Nvidia’s advanced semiconductors.

Given that their sale to China has now been blocked by Washington, expect “high-quality development” to evolve into “new quality productive forces” – a new slogan introduced by Xi in 2023, which shifts the focus more toward domestic pride and national security.

This means positioning China at the cutting edge of chip-making, computing, and AI – independent of Western technology and impervious to embargoes.

Self-sufficiency in all areas, particularly at the highest echelons of innovation, is likely to be a central tenet of the next Five-Year Plan.

“National security and technological independence are now the defining mission of China’s economic policy,” Mr. Thomas explains.

“Again, it harkens back to the nationalist project that underpins communism in China, to ensure it is never again dominated by foreign countries.”

For more on this story, listen to Business Daily: Can China’s debt problem be solved?

A US appeals court rules to halt a judge’s order that blocked the deployment while a challenge to Trump’s action plays out.

The US and Australia agreed to a framework that includes investments in projects to expand mining and processing of rare earth and critical minerals.

In 2020, Kevin Rudd wrote on social media that he believed Trump was the ‘most destructive’ president in US history.

The department, tasked with safeguarding the US nuclear stockpile, has never before furloughed workers.

Beijing has avoided any sharp downturn but faces economic challenges including US tariffs.

“`