“`html

The Allahabad High Court, a venerable institution in India’s legal system with a history graced by figures like Jawaharlal Nehru and future Supreme Court justices, is once again the subject of public discourse.

However, the reasons for this renewed attention are markedly different from its storied past.

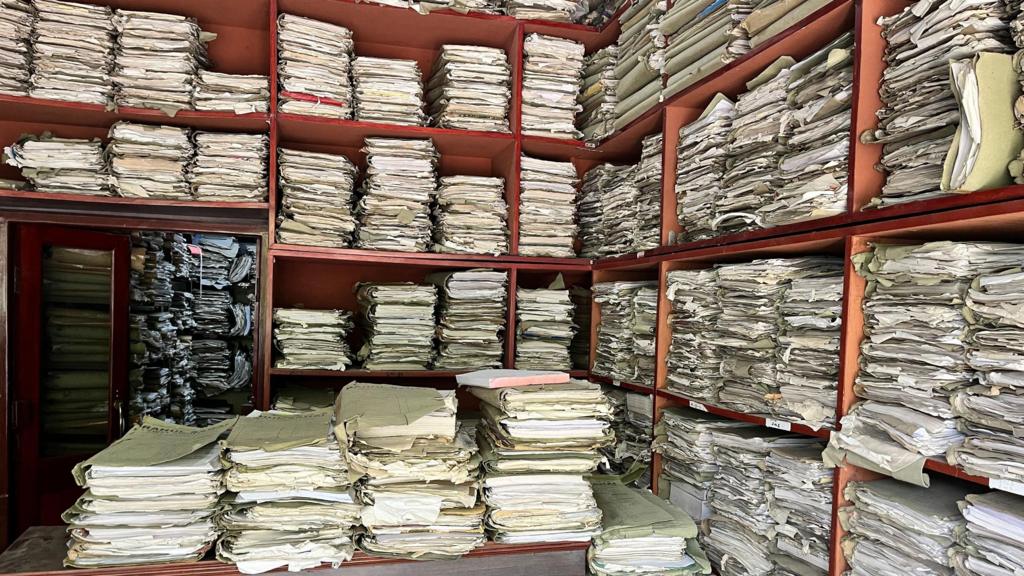

Burdened by a staggering backlog exceeding one million cases, the Allahabad High Court stands as one of the most overwhelmed judicial bodies in the nation. Criminal trials, property disputes, and family matters have languished for decades, leaving countless residents of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, trapped in protracted legal uncertainty.

Consider the plight of Babu Ram Rajput, a 73-year-old retired government employee, who has been embroiled in a property dispute for over three decades.

Having acquired land at auction in 1992, Mr. Rajput’s ownership was challenged by the previous owner, and the case remains unresolved to this day.

“I can only hope that my case is resolved while I am still alive,” Mr. Rajput laments.

The challenges faced by the Allahabad High Court reflect a broader crisis within India’s judiciary, where a persistent shortage of judges coupled with a relentless influx of cases has resulted in debilitating delays.

With a sanctioned strength of 160 judges, a figure that experts assert has never been fully realized, the court is significantly understaffed. Moreover, delays in police investigations, frequent adjournments, and inadequate infrastructure exacerbate the backlog, pushing the system beyond its operational capacity.

Each judge is burdened with hundreds of cases daily, sometimes exceeding 1,000. Given a mere five working hours, this equates to less than a minute per case. In reality, many cases remain unheard.

Legal professionals report that urgent matters, such as bail applications and eviction stays, receive priority, relegating older cases further down the docket.

Senior lawyer Syed Farman Naqvi explains that courts often issue interim or temporary orders in pressing cases, but once the immediate need is addressed, the matter stagnates as new cases continue to accumulate.

Retired judge Amar Saran notes that the escalating backlog has compelled judges to adopt a “cut-grass approach,” issuing swift, standard orders ranging from urging government action to directing lower courts to manage the matter.

In April, the court confronted the stark reality of its delays while ruling on a rape and murder case pending for over 40 years. By the time the verdict was delivered, four of the five convicted individuals had died. The court, ordering the sole surviving convict to surrender, acknowledged its regret for the delayed ruling.

The backlog has even spurred legal action. Earlier this year, a group of Allahabad High Court lawyers filed a petition seeking more judicial appointments, decrying the court as “paralyzed” by a shortage of judges, resulting in years-long case delays.

The crisis has garnered the attention of India’s highest court. In January, the Supreme Court expressed concern over the unpredictable case listings at the Allahabad High Court, stating that the system had effectively collapsed.

Uncertain hearing dates disproportionately affect individuals, particularly in the expansive state of Uttar Pradesh. Many travel hundreds of kilometers to Prayagraj, where the court is located, often with minimal notice for their hearing.

Mr. Rajput resides in Kanpur, approximately 200km (125 miles) from Prayagraj. He spends about four hours traveling each time his case is listed, with no guarantee that it will actually be heard.

“I am over 70,” he states. “I often receive notice of my case listing just days in advance, making travel arduous.” He adds that his case is frequently adjourned because other matters consume the entire day.

Legal professionals have long advocated for the establishment of another bench, a branch of the high court in a different city, to improve accessibility and expedite hearings in the western part of the state. Currently, an additional bench exists in Lucknow. A similar recommendation was made in 1985 by a government commission but has not been implemented.

Earlier this year, the state government reportedly urged the high court to establish another bench, but the letter was subsequently withdrawn for undisclosed reasons. The call for additional benches extends beyond Uttar Pradesh; a 2009 Law Commission report suggested that all states would benefit from additional high court branches.

While new benches could offer long-term relief, experts emphasize the need for more immediate solutions, such as appointing more judges.

However, the appointment process is protracted and complex: senior high court judges first shortlist candidates, followed by reviews by the state and federal governments, and the Chief Justice of India. Subsequently, senior Supreme Court judges forward the final list to the federal government for appointment.

Experts note that identifying suitable candidates is often challenging. Former Allahabad High Court Chief Justice Govind Mathur points out that chief justices, often appointed from outside the state, may lack familiarity with local lawyers or judges, complicating recommendations. Nominations can be rejected at any stage and remain confidential until the Supreme Court forwards them to the government.

Last year, the Supreme Court recommended only one appointment for the Allahabad High Court, despite nearly half the seats being vacant. Some progress occurred this year, with the addition of 40 new judges, 24 of whom were appointed last week, but the backlog persists.

Experts estimate that, even at full capacity, each judge would still be responsible for over 7,000 pending cases.

Mr. Mathur argues that deeper judicial reforms, such as a “uniform policy for hearing and disposing of cases,” are crucial, rather than relying on individual judges.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.

The designation allows law enforcement to seize property and freeze money owned by the group in the country.

At least 40 people died over the weekend in a crowd crush at a political rally organised by Vijay’s party.

Fixtures, results and scorecards from West Indies’ two-Test tour of India.

India beat Pakistan by five wickets in a tense final to retain the Asia Cup at the Dubai International Cricket Stadium.

Tens of thousands had gathered at a campaign event for actor-turned-politician Vijay in India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu.

“`