“`html

What does it mean to live in exile?

“When we were in school, our teachers used to say that there is an ‘R’ on our forehead – meaning refugees,” reflects Tenzin Tsundue, a Tibetan writer and activist.

Mr. Tsundue is one of approximately 70,000 Tibetans residing in India, dispersed across 35 designated settlements.

In 1959, a failed uprising against Chinese rule prompted thousands of Tibetans to flee.

Following their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, they traversed perilous Himalayan passes to reach India, where they were granted refuge on humanitarian grounds and due to shared religious and cultural affinities.

However, Mr. Tsundue asserts that living, or even being born, in India does not equate to being Indian.

Tibetans in India are required to possess renewable registration certificates, which are issued every five years. Those born in India may apply for passports if a parent was born in India between 1950 and 1987, but doing so necessitates surrendering the certificate. Many are hesitant, as the certificate is deeply intertwined with their Tibetan identity.

In July, as the Dalai Lama celebrated his 90th birthday, thousands of Tibetan Buddhists convened in Dharamshala, a tranquil town nestled in the Himalayan foothills of Himachal Pradesh, a northern Indian state. The town serves as the headquarters of the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), the Tibetan government-in-exile.

Even as they offered prayers for their leader’s longevity, many, including Mr. Tsundue, found themselves contemplating the precariousness of life in exile.

The emotional burden of displacement, the legal ambiguity of statelessness, and the geopolitics surrounding the Dalai Lama cast a somber shadow over the birthday celebrations.

Tibetans continued to migrate to India for decades after 1959, escaping China’s escalating control over their homeland.

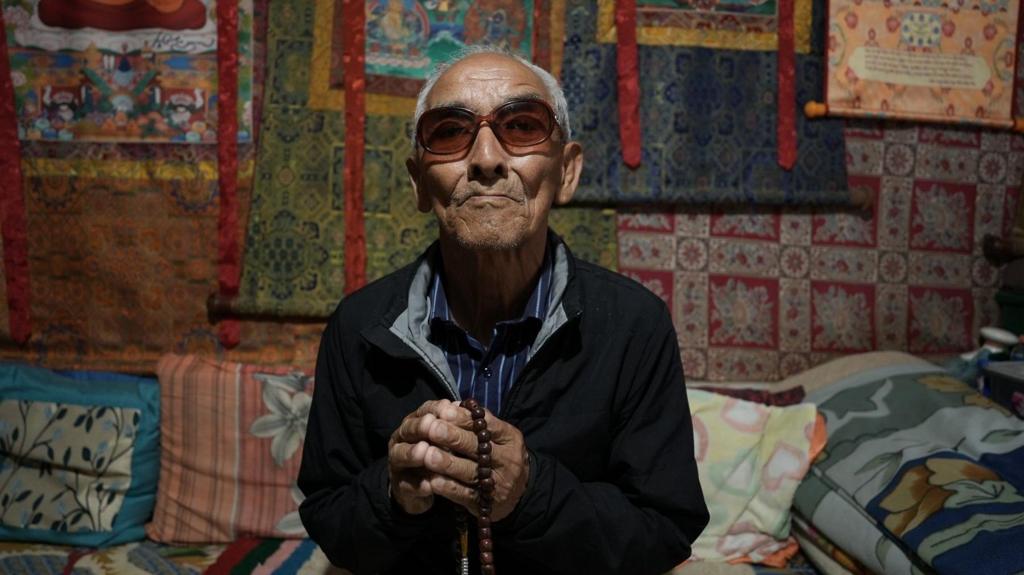

Dawa Sangbo, 85, arrived in Dharamshala in 1970 after enduring a grueling seven-day trek through Nepal. “We ran at night and hid by day,” he recounts.

Lacking accommodation in India, he spent 12 years living in a tent and selling spices in villages near Dharamshala to survive. He now resides with his son and wife in a neighborhood predominantly inhabited by Tibetans.

For many like Mr. Sangbo, seeking refuge in India may have provided safety, yet they continue to long for their homeland.

“A home is a home, after all,” says Pasang Gyalpo, who fled Tibet to Nepal before settling in India in 1990.

Five years later, Mr. Gyalpo bribed Nepalese guards and secretly re-entered Tibet to bring his family to India. However, Chinese police pursued him shortly after his arrival, compelling him to flee. His family remains in Tibet.

“They are in their homeland, I am in a foreign land. What else can I feel but pain?” he laments.

For younger Tibetans like Mr. Tsunde, who were born in India, the pain is more existential.

“The trauma for us is not that we lost our land,” he explains. “It’s that we were not born in Tibet and don’t have the right to live in Tibet. It is also this great sense of deprivation that something so very essential of our land, culture, and language has been taken away from us.”

Lobsang Yangtso, a researcher specializing in Tibet and Himalayan regions, elucidates that being stateless engenders a lack of belonging.

“It’s painful,” she says. “I have lived all my life here [in India] but I still feel homeless.”

Tibetans in exile express gratitude to India for providing refuge, but lament their limited rights, including the inability to vote, own property, or readily travel abroad without an Indian passport.

“We have the IC [an official travel document] which is given by the Indian government as an identity certificate,” says Phurbu Dolma. However, airport immigration personnel often do not recognize it.

Dorjee Phuntsok, a Tibetan born in India, notes that numerous corporate positions in India necessitate Indian passports. “Without one, we miss out on many opportunities.”

In recent years, a significant number of Tibetans in India have emigrated to Western countries using the IC, which some nations accept for visa applications.

Many have departed on student or work visas, resettled in countries such as the US and Canada, or traveled abroad under the sponsorship of religious and humanitarian organizations.

Penpa Tsering, the president of the CTA, attributes the emigration primarily to economic factors. “Dollars and euros go further than what’s available here,” he says.

However, for some, like Thupten Wangchuk, 36, who crossed over to India as an eight-year-old, the motivation is more personal.

“For [almost] 30 long years, I haven’t met my parents and relatives. I’ve no one here,” he says. “The sole reason I want to go to a Western country is that I can become a citizen there. Then I can apply for a visa and go into Tibet to visit my parents.”

Some Tibetans acknowledge the necessity of being pragmatic, given the prevailing geopolitical pressures.

“If you ask any Tibetan, they’ll say they want to go back,” says Kunchok Migmar, a CTA official. “But right now, there is no freedom in Tibet. No one wants to go back just to be beaten by the Chinese.”

A recent point of contention arose just days before the Dalai Lama’s 90th birthday. He stated that his successor would be chosen by a trust under his office, a decision rejected by China, which insisted that it would make the determination under its own laws. Beijing characterized the succession issue as a “thorn” in its relationship with India.

India’s official stance is that it “does not take any position concerning beliefs and practices of faith and religion.” Notably, two senior ministers of the Indian government shared the stage with the Dalai Lama on his birthday.

The Dalai Lama’s announcement regarding a successor brought a sense of relief among Tibetans. However, uncertainty remains regarding the potential impact of his death on the Tibetan movement.

“If we prepare ourselves well from now, when His Holiness is alive and [if] the future leaders who will follow us can continue the same momentum, then I think it should not affect us as much as people think it could,” says Mr. Tsering.

His optimism is not universally shared among Tibetans.

“It’s thanks to the current Dalai Lama that we have these opportunities and resources,” says Mr. Phuntsok. He adds that many Tibetans fear that, following his passing, the community may lose the long-standing support that has sustained them.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.

There is a risk of community tensions escalating in Epping, the authority says.

A government minister describes the number as “unacceptable” but says Labour is “making progress”.

Sir Keir Starmer has promised to “smash the gangs” which smuggle people across the English Channel.

Rescue operations at the disaster site have been hampered by heavy rains and blocked roads.

India tackles the problem of making AI translate between its many languages and dialects

“`