“It’s unfair to lift censorship suddenly,” a seasoned newspaper editor purportedly grumbled, according to a cartoon, with “The Daily Pulp” splayed across his desk. “We should be given time to prepare our minds.”

This poignant and satirical cartoon is the work of Abu Abraham, widely regarded as one of India’s foremost political cartoonists. His incisive pen elegantly skewered those in power, particularly during the 1975 Emergency, a 21-month period when civil liberties were suspended and the media was silenced under Indira Gandhi’s government.

On June 25th, the press was abruptly muzzled. Newspaper presses in Delhi were shut down, and by morning, censorship was the law of the land. The government demanded subservience from the press – and, as opposition leader LK Advani famously quipped, many “chose to crawl.”

Another well-known cartoon from that era, signed simply “Abu,” depicts a man inquiring of another: “What do you think of editors who are more loyal than the censor?”

Remarkably, half a century later, Abu’s cartoons continue to resonate.

India currently holds the 151st position in the World Press Freedom Index, an annual assessment compiled by Reporters Without Borders. This ranking reflects growing concerns regarding media independence under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration. Critics allege increased pressure and attacks on journalists, media acquiescence, and a diminishing space for dissenting opinions. The government refutes these claims, maintaining that the media remains free and vibrant.

After a nearly 15-year stint drawing cartoons in London for The Observer and The Guardian, Abu returned to India in the late 1960s. He joined the Indian Express newspaper as a political cartoonist during a period of intense political turmoil.

He later recounted that pre-censorship, which mandated that newspapers and magazines submit news reports, editorials, and even advertisements to government censors prior to publication, commenced two days after the Emergency was declared. It was lifted briefly after a few weeks, then reimposed a year later for a shorter duration.

“For the rest of the time I had no official interference. I have not bothered to investigate why I was allowed to carry on freely. And I am not interested in finding out.”

Many of Abu’s Emergency-era cartoons are iconic. One depicts then-President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signing the proclamation from his bathtub, capturing the haste and nonchalance with which it was issued (Ahmed signed the Emergency declaration that Gandhi had issued shortly before midnight on June 25).

Among Abu’s most striking works are several cartoons boldly stamped with “Not passed by censors,” a stark symbol of official suppression.

In one, a man holds a placard reading “Smile!” – a subtle jab at the government’s forced-positivity campaigns during the Emergency. His companion retorts drily, “Don’t you think we have a lovely censor of humour?” – a line that encapsulates the essence of state-enforced cheer.

Another seemingly innocuous cartoon portrays a man at his desk sighing, “My train of thought has derailed.” Yet another features a protester holding a sign that reads “SaveD democracy” – the “D” awkwardly appended, as if democracy itself were an afterthought.

Abu also targeted Sanjay Gandhi, Indira Gandhi’s unelected son, who was widely believed to have run a shadow government during the Emergency, wielding unchecked power. Sanjay’s influence was both controversial and widely feared. He died in a plane crash in 1980 – four years before his mother, Indira, was assassinated by her bodyguards.

Abu’s work was deeply political. “I have come to the conclusion that there’s nothing non-political in the world. Politics is simply anything that is controversial and everything in the world is controversial,” he wrote in Seminar magazine in 1976.

He also lamented the state of humor – strained and artificial – when the press was gagged.

“If cheap humour could be manufactured in a factory, the public would rush to queue up in our ration shops all day. As our newspapers become progressively duller, the reader, drowning in boredom, clutches at every joke. AIR [India’s state-run radio station] news bulletins nowadays sound like a company chairman’s annual address. Profits are carefully and elaborately enumerated, losses are either omitted or played down. Shareholders are reassured,” Abu wrote.

In a tongue-in-cheek column for the Sunday Standard in 1977, Abu satirized the culture of political obsequiousness with a fictional account of a meeting of the “All India Sycophantic Society.”

The spoof featured the society’s imaginary president declaring: “True sycophancy is non-political.”

The satirical monologue continued with mock pronouncements: “Sycophancy has a long and historic tradition in our country… ‘Servility before self’ is our motto.”

Abu’s parody culminated in the society’s guiding vision: “Touching all available feet and promoting a broad-based programme of flattery.”

Born Attupurathu Mathew Abraham in the southern state of Kerala in 1924, Abu began his career as a reporter at the nationalist Bombay Chronicle, driven less by ideology than a fascination with the power of the printed word.

His reporting years coincided with India’s dramatic journey to independence, witnessing firsthand the euphoria that gripped Bombay (now Mumbai). Reflecting on the press, he later noted, “The press has pretensions of being a crusader but is more often a preserver of the status quo.”

After two years with Shankar’s Weekly, a well-known satire magazine, Abu set his sights on Europe. A chance encounter with British cartoonist Fred Joss in 1953 propelled him to London, where he quickly made a name for himself.

His debut cartoon was accepted by Punch within a week of arrival, earning praise from editor Malcolm Muggeridge as “charming.”

Freelancing for two years in London’s competitive scene, Abu’s political cartoons began appearing in Tribune and soon caught the attention of The Observer’s editor, David Astor.

Astor offered him a staff position with the paper.

“You are not cruel like other cartoonists, and your work is the kind I was looking for,” he told Abu.

In 1956, at Astor’s suggestion, Abraham adopted the pen name “Abu,” writing later: “He explained that any Abraham in Europe would be taken as a Jew and my cartoons would take on slant for no reason, and I wasn’t even Jewish.”

Astor also assured him of creative freedom: “You will never be asked to draw a political cartoon expressing ideas which you do not yourself personally sympathise.”

Abu worked at The Observer for 10 years, followed by three years at The Guardian, before returning to India in the late 1960s. He later wrote he was “bored” of British politics.

Beyond cartooning, Abu served as a nominated member of India’s upper house of Parliament from 1972 to 1978. In 1981, he launched Salt and Pepper, a comic strip that ran for nearly two decades, blending gentle satire with everyday observations. He returned to Kerala in 1988 and continued to draw and write until his death in 2002.

But Abu’s legacy was never solely about the punchline—it was about the deeper truths his humor revealed.

As he once remarked, “If anyone has noticed a decline in laughter, the reason may not be the fear of laughing at authority but the feeling that reality and fancy, tragedy and comedy have all, somehow got mixed up.”

That blurring of absurdity and truth often gave his work its edge.

“The prize for the joke of the year,” he wrote during the Emergency, “should go to the Indian news agency reporter in London who approvingly quoted a British newspaper comment on India under the Emergency, that ‘trains are running on time’ – not realising this used to be the standard English joke about Mussolini’s Italy. When we have such innocents abroad, we don’t really need humorists.”

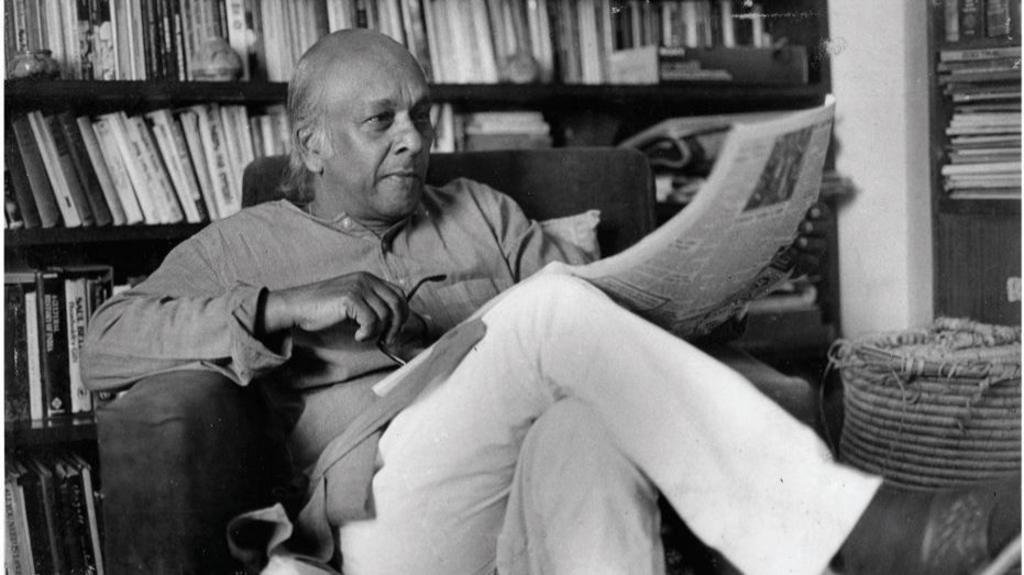

Abu’s cartoons and photograph, courtesy Ayisha and Janaki Abraham

The F-35B landed in Kerala on 14 June after running into bad weather. It then reported a technical snag.

India spin bowler R Sai Kishore joins Surrey for the club’s next two County Championship games.

Michael Vaughan says he has concerns before England’s third Test against India, saying any changes to the hosts’ line-up will be a “risk” at Lord’s.

Former England bowler and BBC Sport pundit Steven Finn explains why England tried to get the ball changed on a number of occasions during the second Test at Headingley.

Coach Brendon McCullum says England “probably” made a mistake in deciding to bowl first during their 336-run defeat by India in the second Test at Edgbaston.